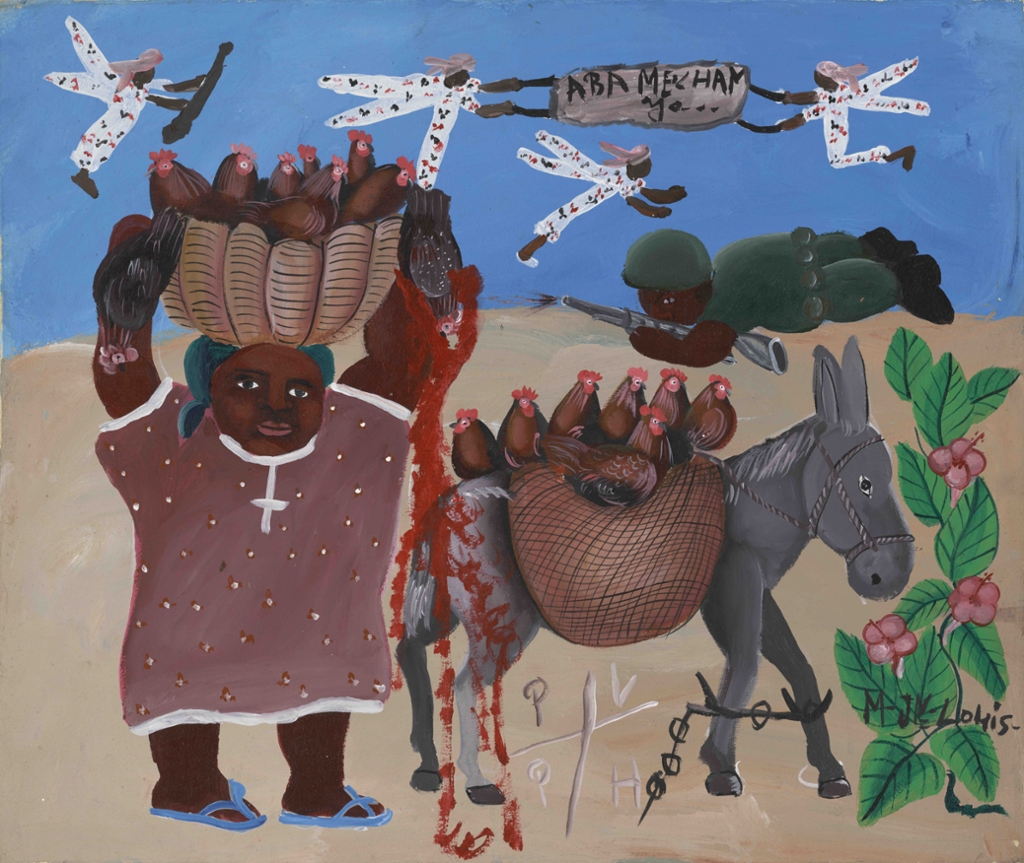

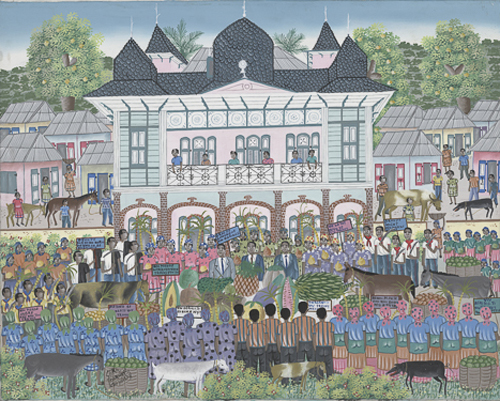

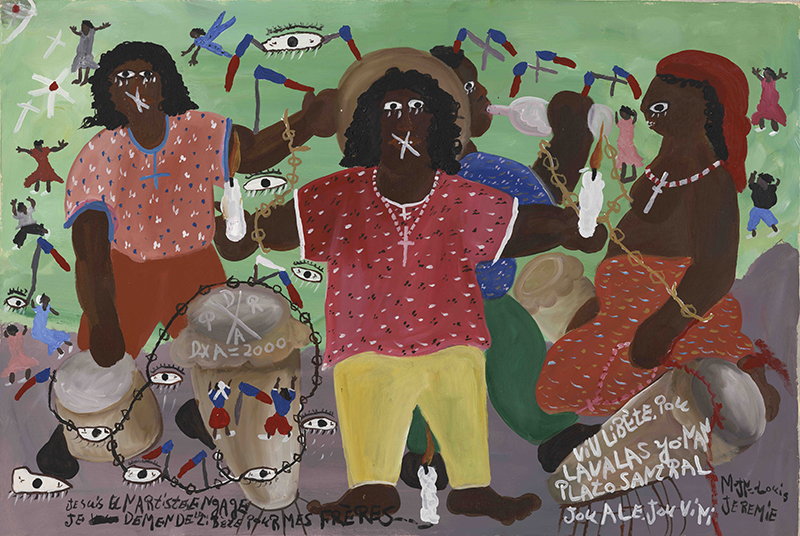

Roland St. Hubert, Haitian, b.1951, Untitled, Oil on canvas, 1989, Gift of Louis Paolino, Mt. Laurel, FIU 95.05.15

From a young age, St. Hubert was interested in art and started painting formally in his early 20s. By comparing his artworks one finds a common theme and style among them. St. Hubert frequently uses bright color palettes, nonetheless, for this work he used a combination of both dark and bright colors to portray the crucifixion. The marriage of both palettes may symbolize peace and chaos amongst the people. The use of yellow may represent God as it shines down on the man on the cross. The use of orange can be seen as a form of protection as it separates the woman from the rest of the painting.

Roland St. Hubert, Haïtien, né 1951, Sans titre, Huile sur toile, 1989, Don de Louis Paolino, Mt. Laurel, FIU 95.05.15

Dès son plus jeune âge, St. Hubert s’intéresse à l’art et commence à peindre professionnellement au début de ses 20 ans. Bien qu’il y ait peu de renseignements disponibles sur cet artiste, en comparant ses œuvres, on peut y voir un thème et un style communs. Saint Hubert utilise fréquemment des palettes de couleurs vives, néanmoins, pour cette œuvre, il utilise une combinaison de couleurs sombres et vives pour représenter la crucifixion. Le mariage des deux palettes peut symboliser la paix et le chaos parmi les gens. L’utilisation du jaune peut représenter Dieu illuminant l’homme sur la croix. L’utilisation de la couleur orange peut être considérée comme une forme de protection car elle sépare la femme du reste du tableau. Saint Hubert utilise des techniques différentes pour donner vie à sa peinture et pour souligner ses contrastes.

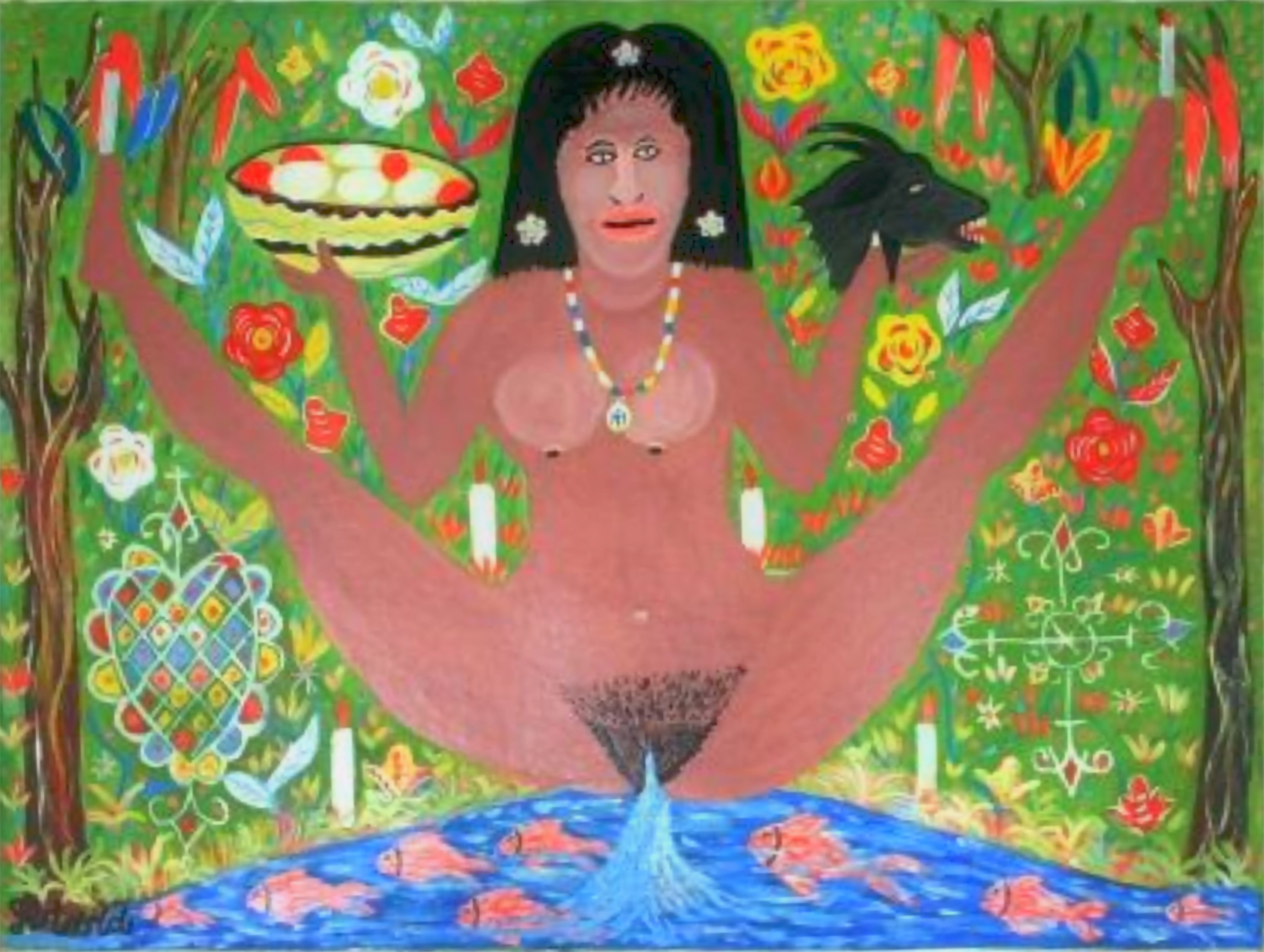

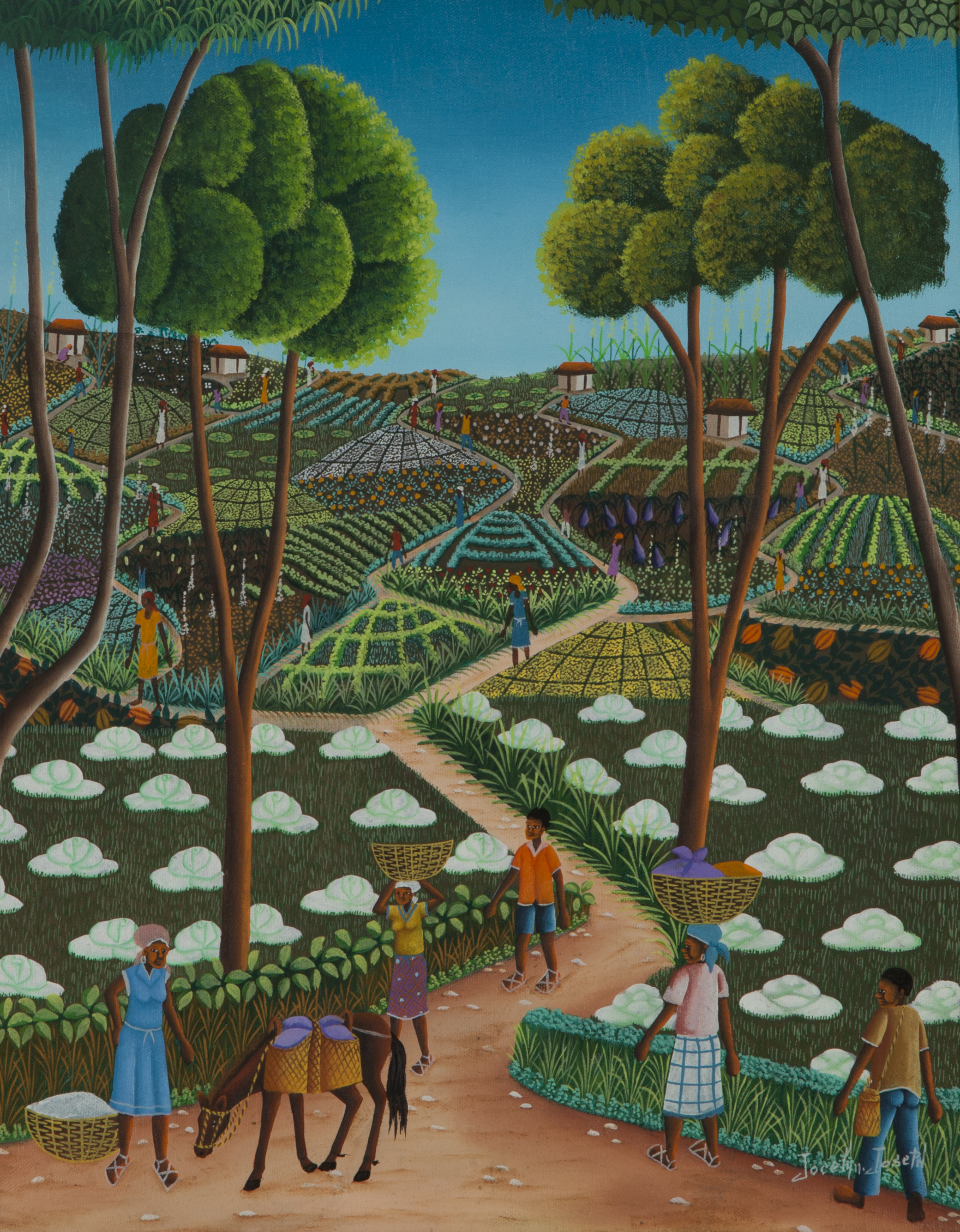

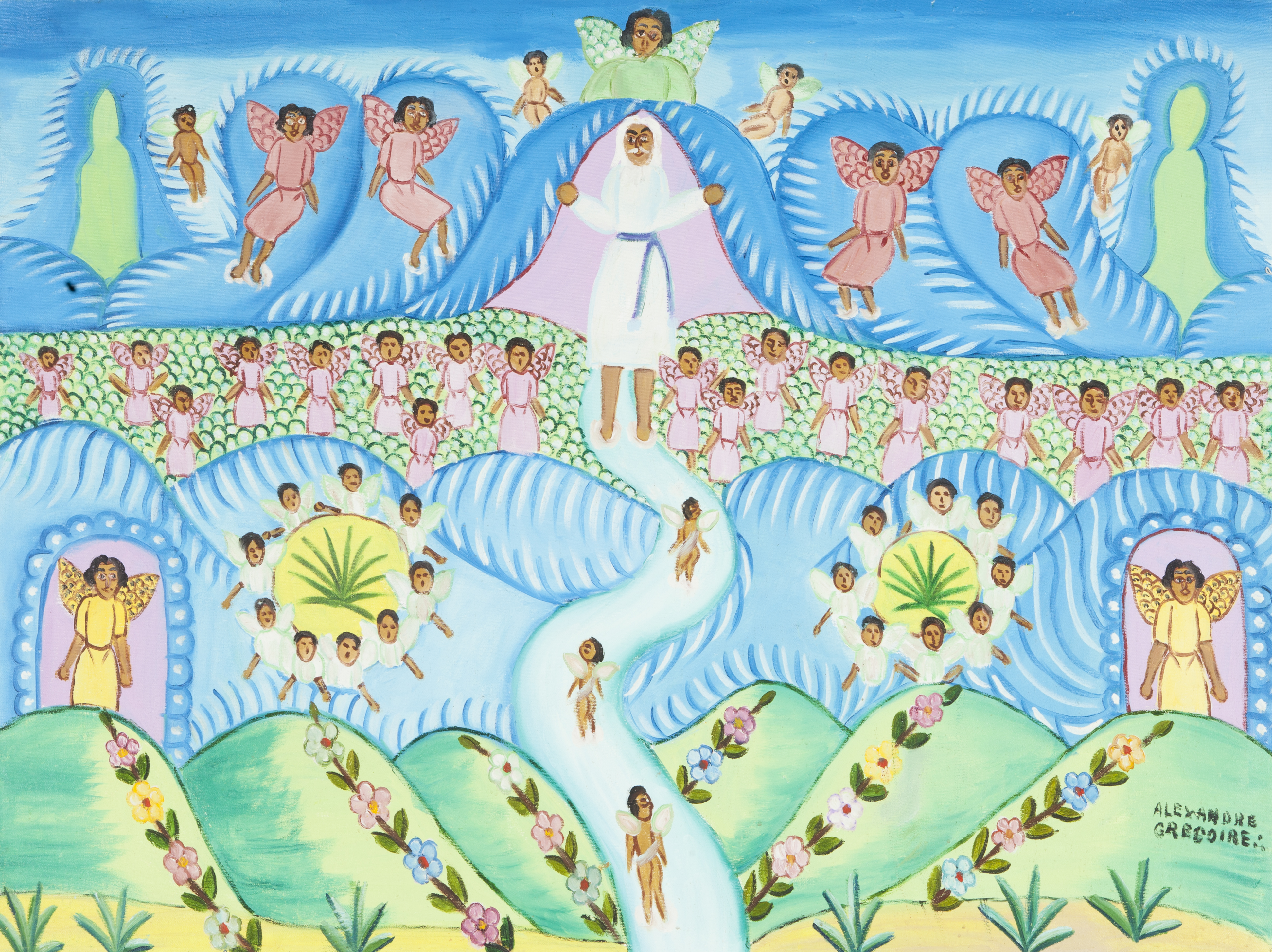

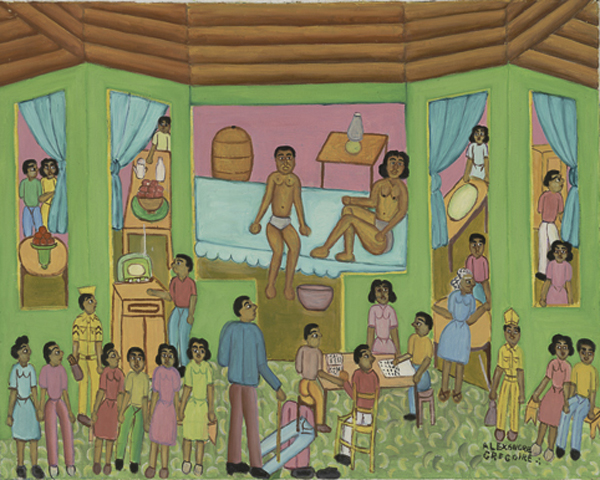

Gérard Fortuné, Haitian, 1924–2019, Elegant Mermaid, Oil on canvas, c.1984, Gift of Raymond and Judi Richards, FIU 1999.019.076

Gérard Fortuné began his career as a painter in 1978. He was a self-taught artist who devoted his life’s work to portray Haitian life, vodou, Christian imagery, and everything that inspired him, as he stated: “I’m obligated to paint vodou and Jesus and flowers and the sea. And villages and anything that comes to mind.” He was also a houngan or a vodou priest. Kanaval, the Haitian Creole carnival, was one of the main influences for the artist, adding playful and vibrant colors to his works of art. Many of his paintings show La Sirène (the mermaid) at the intersection of terrestrial life and ocean cosmology, as in this painting. Water dominates Haitian life, and La Sirène offers protection to the sailors. The Lord of the Water is Agwé, and his consort is La Sirène. In vodou religion, a mermaid is a Loa (or Lwa), a god, spirit, genius. The Haitian mermaid, La Sirène, is characterized by her long black hair, representing feminine beauty and elegance. The followers of vodou religion give offerings to La Sirène to gain her favor. Some common offerings brought to her are flowers, in exchange, she has the power to help them gain prosperity, good luck, health, and above all love.

Gérard Fortuné, Haïtien, 1924–2019, Sirène élégante, Huile sur toile, vers 1984, Don de Raymond et Judi Richards, FIU 1999.019.076

Gérard Fortuné a commencé sa carrière de peintre en 1978. C'était un artiste autodidacte qui a consacré sa vie à dépeindre la vie haïtienne, le vaudou, l'imagerie chrétienne, et tout ce qui l'a inspiré, comme il l'a déclaré : « Je suis obligé de peindre le vaudou et Jésus et les fleurs et la mer. Et les villages et tout ce qui me vient à l'esprit. » Il était aussi un houngan ou prêtre vaudou. Kanaval, le carnaval créole haïtien, a été l'une des principales influences pour cet artiste, ajoutant des couleurs ludiques et vibrantes à ses œuvres d'art. Plusieurs de ses tableaux montrent La Sirène à l'intersection de la vie terrestre et de la cosmologie océanique, comme dans ce tableau. L'eau domine la vie haïtienne, et La Sirène offre une protection aux marins. Le Seigneur de l'Eau est Agwé, et son épouse est La Sirène. Dans la religion vaudou, une sirène est un Loa (ou Lwa), un dieu, un esprit, un génie. L'une des caractéristiques de la sirène haïtienne, La Sirène, est qu'elle a de longs cheveux noirs, représentant la beauté et l'élégance féminines. Les adeptes de la religion vaudou font des offrandes à La Sirène pour gagner sa faveur. Quelques offrandes courantes qui lui sont apportées sont des fleurs, en échange, elle a le pouvoir de les aider à gagner en prospérité, en chance, en santé et surtout en amour.

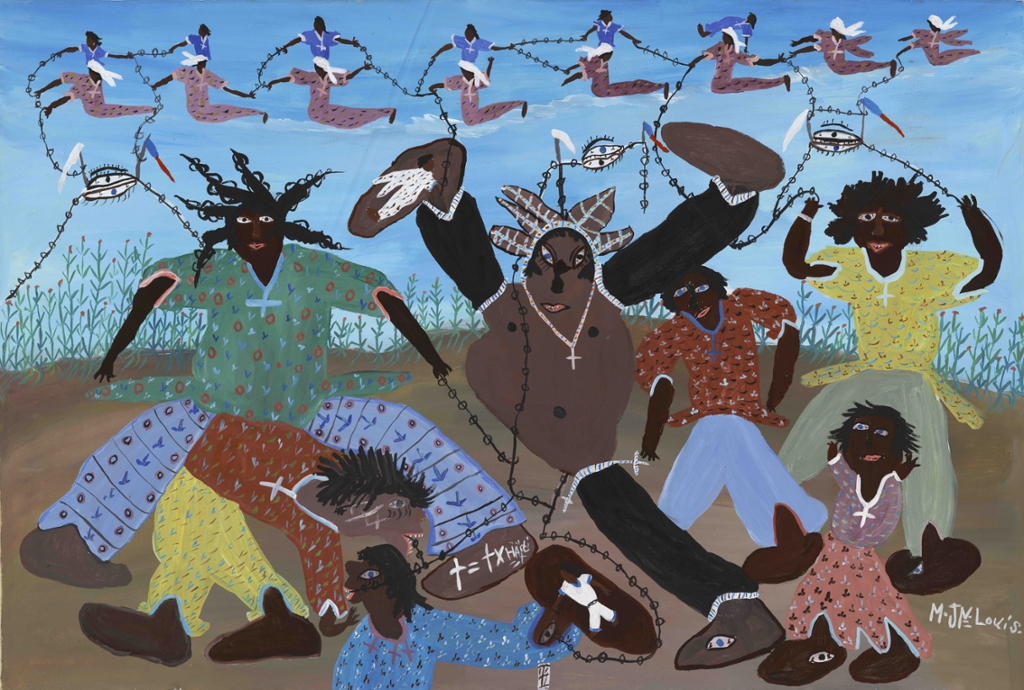

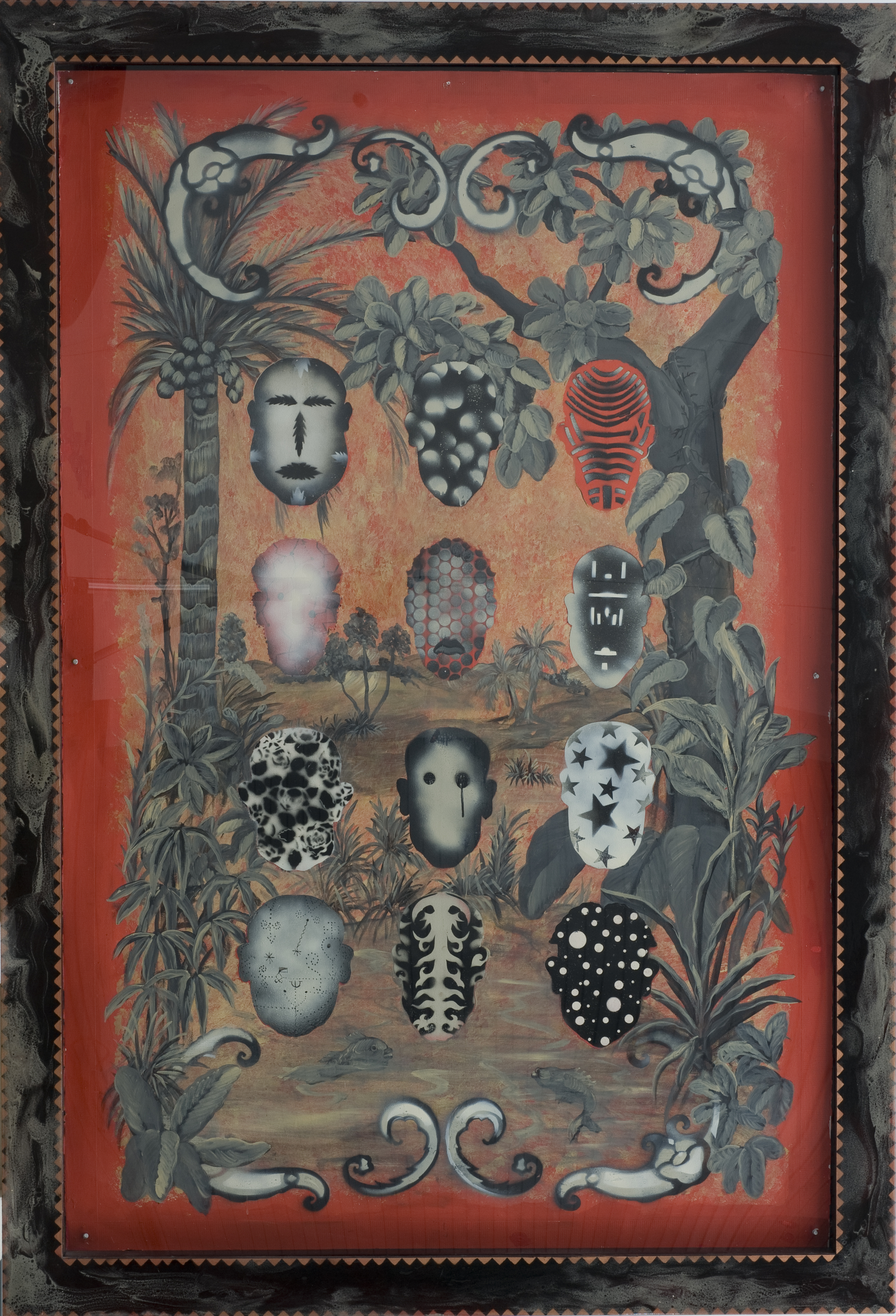

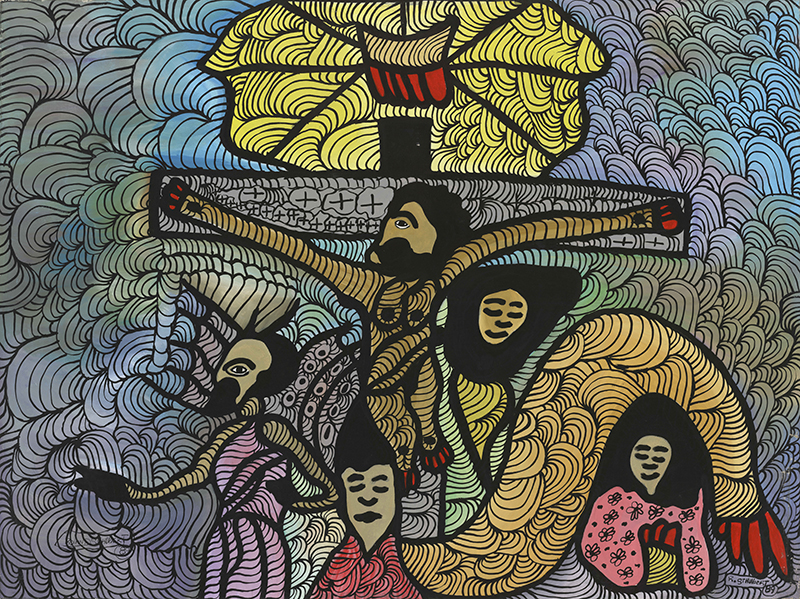

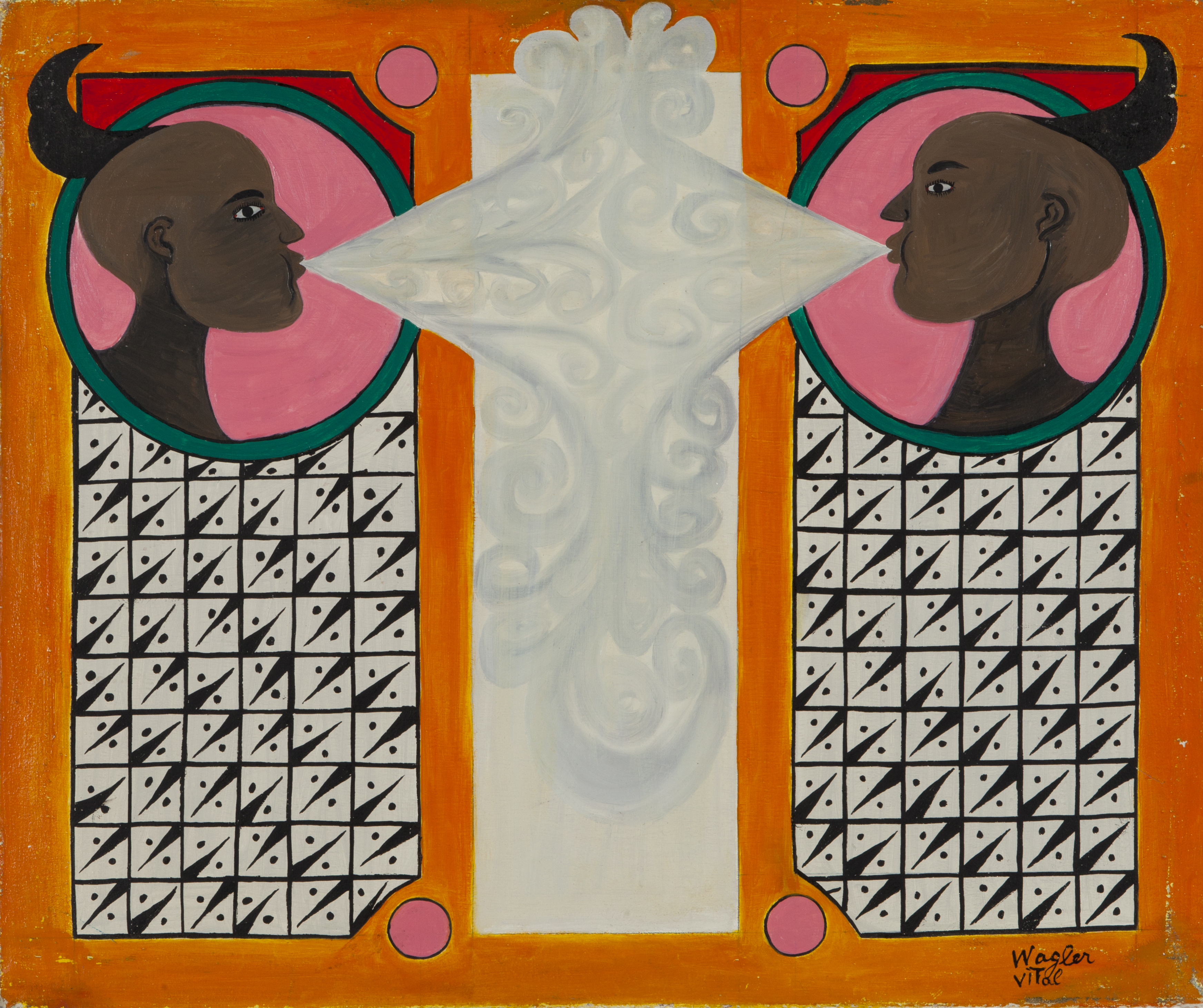

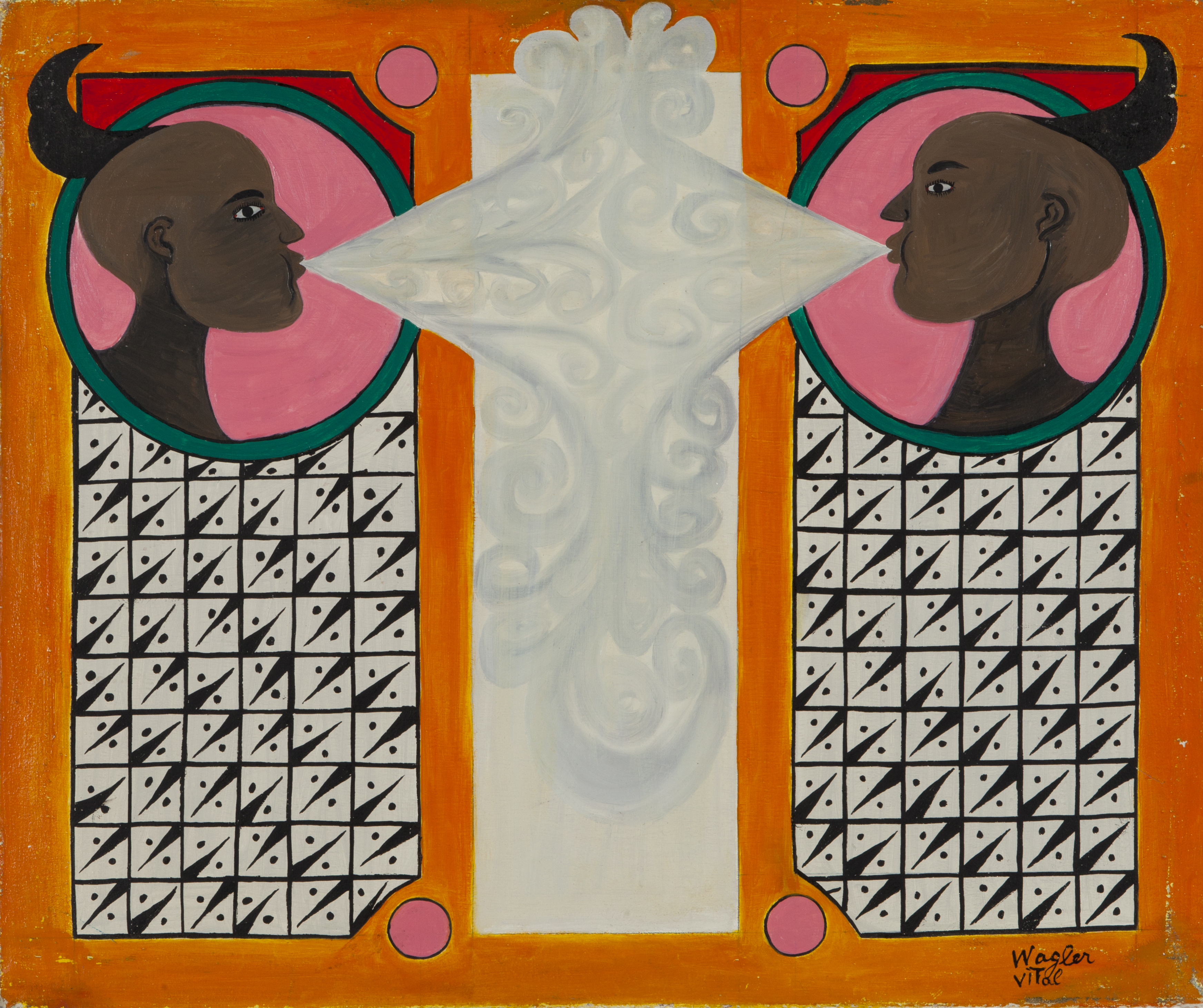

Wagler Vital, Haitian, b.1950, Untitled, Oil on canvas, late 20th century, Gift of Ashvin Rajan, FIU 95.15.83

Wagler Vital was born in Haiti, and lives in Port-au-Prince. He is heavily influence in his art by vodou themes. Originally a mason by trade, Vital was attracted to painting because of his interest in vodou. His art was influenced by many artists, but one of his main influences came from the houngan and noted painter André Pierre (c.1915–2005). His own style is reflected in his paintings and vodou flags, but Vital is one of the few artists who successfully moved from the sacred art of vodou drapo into the realistic depiction of the vodou ceremony in the form of painting. In this work, we can see the blowing or exhaling from one body against another. In vodou practice, as well as in many other religions, blowing or exhaling means the expulsion of evil and unclean spirits from within the body to be set free; in turn, inhaling means breathing in all the good. Since in this painting there are two men blowing against each other, this can be interpreted a conflict or a discontent between the two, as in releasing all bad things against each other. In turn, the symmetry is notable in this painting, through many geometric figures such as circles, rectangles, and other forms. In the vodou religion, circles are sometimes painted and drawn for rituals.

Wagler Vital, Haïtien, b.1950, Sans titre, Huile sur toile, fin du 20e siècle, Don d'Ashvin Rajan, FIU 95.15.83

Wagler Vital est né en Haïti et vit à Port-au-Prince. Il est fortement influencé dans son art par les thèmes vaudou. A l'origine maçon de métier, Vital ne pouvait nier son attirance pour la peinture, ni pour son expression du vaudou. Son art a été influencé par de nombreux artistes, mais l'une de ses principales influences principales lui vient du houngan et peintre célèbre André Pierre (c. 1915–2005). Son propre style se reflète dans ses peintures et ses drapo vaudou, mais Vital est l'un des rares artistes à avoir réussi à passer de l'art sacré du drapo vaudou à la représentation réaliste de la cérémonie vaudou sous forme de peinture. Dans cette œuvre, on peut voir le souffle ou l'expiration d'un corps contre un autre. Dans la pratique du vaudou, ainsi que dans de nombreuses autres religions, souffler ou expirer signifie l'expulsion des esprits mauvais et impurs de l'intérieur du corps pour être libérés ; à son tour, inhaler signifie respirer tout le bien. Comme dans ce tableau il y a deux hommes qui soufflent l'un contre l'autre, cela peut être interprété comme un conflit ou un mécontentement entre les deux, comme une libération de toutes les mauvaises choses de l’un contre l'autre. À son tour, la symétrie est notable dans cette peinture, à travers de nombreuses figures géométriques telles que des cercles, des rectangles et d'autres formes. Dans la religion vaudou, des cercles sont parfois peints et dessinés pour des rituels.

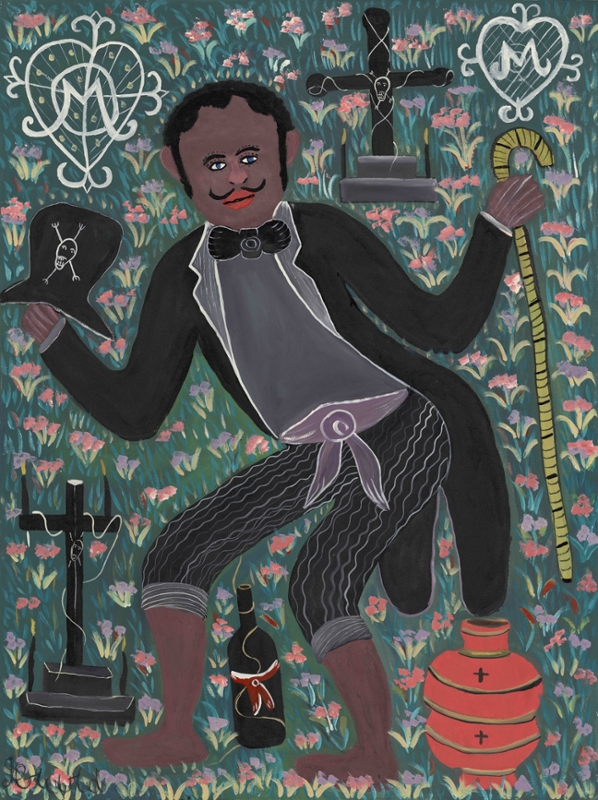

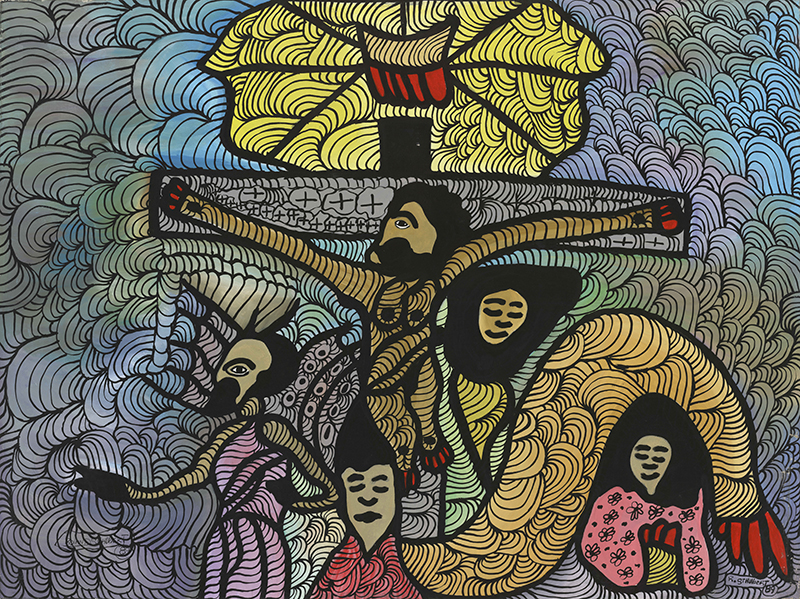

Unknown artist, Haitian, Vodou Flag: Makaya, Sequins, cloth, late 20th century, FIU 1999.021.004

Haitian vodou is an African diasporic religion which expanded in Haiti between the 16th and19th centuries. It began by blending West and Central African as well as the Roman Catholicforms of Christianity. Vodou revolves around spirits known as lwa. This composition representsa rite in Haitian vodou which is referred to as Makaya. The man in the artwork depicts granbwa,a lwa. The coffin with the cross on top suggests that Makaya is associated with secret societies –sanpwel groups. The cross represents a supporting framework around which the universe isconstructed. The three-legged pot symbolizes the pharmacy utilized to prepare medication. Thetchatcha refers to a vodou instrument used to call spirits during rituals. This work portrays theMakaya tradition which is based on magic, prayer, and sacrifice.

Artiste inconnu, Haïtien, Drapo vodou: Makaya, Paillettes, tissu, 20e siècle, FIU 1999.021.004

Le vaodou haïtien est une religion de la diaspora africaine qui s'est développée en Haïti entre les XVIe et XIXe siècles. Il s’agit d’un mélange d'Afrique de l’ouest et d’Afrique centrale avec les formes catholiques romaines du christianisme. Le vaudou tourne autour des esprits connus sous le nom de lwa. Cette composition représente un rite du vaudou haïtien appelé Makaya. L'homme dans l'œuvre représente granbwa, un lwa. Le cercueil avec la croix au-dessus suggère que Makaya est associé à des sociétés secrètes – des groupes de sanpwel. La croix représente un cadre de support autour duquel l'univers est construit. Le pot à trois pieds symbolise le laboratoire pharmaceutique du vaudou. Le tchatcha fait référence à un instrument du vaudou utilisé pour appeler les esprits lors des rituels. Ce travail dépeint la tradition Makaya qui est basée sur la magie, la prière et le sacrifice.