Coconut Grove Historic Map

In partnership with FIU’s GIS Center, the Frost Art Museum presents a digital map of significant locations in Coconut Grove. From bars and bookstores to churches and schools, these sites testify to the rich history of Coconut Grove.

Coconut Grove Oral History Project

For decades, Coconut Grove has attracted artists, writers, and musicians. The Frost has chosen to tell a story of a moment in the Grove’s rich history through a select group of visual artists. The creative life of the Grove sprang from the vibrant people who chose to create in this Miami neighborhood. It is not a single artist or group of artists but the spirit of a community that has contributed to the Grove’s reputation as a wellspring of creativity.

In conjunction with the exhibition Place and Purpose: Art Transformation in Coconut Grove,the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum presents an oral history project that was conducted over several months with different members of the Coconut Grove community.

Banner: Miami News, ‘Grove Mad hatters are bled hatters now’ The winners in the homemade hat contest in the Coconut Grove Festival display their entries after judging. From left are Selma Magram, third place winner; Ted Peters, a judge: Mrs. Julia Follurd, first place; Joyce Bryant of Porgy and Bess cast, also a judge. And Mrs. Eleanor McCufferty (almost hidden by hats and birds), April 23, 1965, courtesy of the HistoryMiami Museum

- Xavier Cortada

Artist and environmental activist Xavier Cortada and the Frost Art Museum’s curatorial assistant Ashlye Valines sat down to discuss memorable places in the Grove and the ways in which urban development impacted Coconut Grove.

This interview was conducted for the exhibition Place and Purpose: Art Transformation in Coconut Grove and took place on April 1, 2021.

Ashlye Valines: Let’s begin with a simple one. Where were you born?

Xavier Cortada: Albany, New York in 1964 to two Cuban refugees who left Miami to find jobs up there.

Ashlye Valines: When did you come to live in Miami?

Xavier Cortada: 1967. I was born in September of ‘64 and in the summer of ‘67 they moved me to Miami and I’ve never left.

Ashlye Valines: Did you live around the grove?

Xavier Cortada: I lived there. So 27th Avenue, it’s called the “Unity Boulevard” because it literally connects all the neighborhoods… There were these 3 neighborhoods the West Coconut Grove, Coconut Grove, and then little Havana just north of the Grove that was clearly a Cuban enclave, and then as you continued north on 27th Avenue, you’d pass Allapattah and then into Brownsville and Liberty City…so Unity Boulevard is what 27th Avenue was named. Most of my adolescence and all of my childhood years was going up and down either 22nd or 27th Avenue, north to south, and Coconut Grove was a major destination for me. Every evening of my life as an elementary school student I spent in the Grove, but not the Grove as you think about it. [For me] the Grove [was] Our Lady of Charity which is the shrine that Cuban exiles built on church property next to Vizcaya, tucked in between Vizcaya, Mercy Hospital, and behind Immaculata High School. There was an empty lot and this priest named Father Roman would convene the Cuban community to this piece of Coconut Grove on the water’s edge and built an entire community of exiles around what is called La Ermita de la Caridad del Cobre, which is roughly translated to “the shrine to our lady of charity the patron saint of Cuba”, so beloved within the Catholic faith and the kind of place that someone like President Obama would go to on “pilgrimages” when he was trying to connect with the Cuban community as he did during his presidency, as well as the pope and everyone else. It’s like a really important cultural, obviously religious, but cultural center for the Cuban community and for a community like my parents, who, in the early ‘70s, were still living in the diaspora without a true understanding on whether or not there would be a return to Cuba. It was a place for hope and a place for community organizing because the priest, who then became a very important bishop and helped at the national level, when Bill Clinton was governor of Arkansas, in trying to quiet down some rioting that was happening with some Mariel prisoners, he became an important spiritual, civic, and community leader. He would organize Cuban exiles to literally come there and then go into each other’s homes, based on the communities in Cuba from where their families came, as a way of building community. I think the reason I’m telling you all this is because, in many ways, Coconut Grove, not because of its proximity, but because it is at the water’s edge, was a place that would welcome people sailing up from the Florida Keys. It was a place of refuge; it was a city before Miami was a city. So, in so many ways, the same comfort that it provided the pioneers at the beginning of the century, it did so again, seven decades later in the 1970s to another group of immigrants, and there was the huge mural built on that shrine, talking about that experience, particularly the rafters who would, occasionally, in the ‘70s, and dramatically, in the ‘90s, land on our shores seeking liberty.

When we talk about Coconut Grove and we talk about different cultural angles to it from a faith perspective, the Hare Krishna group comes up because, throughout the ‘70s and today, there was a temple nearby, but they would come out dressed in their robes, mostly Anglo practitioners, and literally roam the streets of Coconut Grove. When you think about spirituality in the Grove, indisputably you have to think about the Black churches in the West Grove, [and] when you think about spirituality in the Grove your very keen to think about St. Stephens because, of course, it’s anchored right there at the water’s edge. When you think about spirituality in the Grove you have to go just a few yards south and you start getting into the religious and parochial schools, everything from the Congregational Church, which was scary looking because of its buildings and its dramatic lighting. I remember as a high school kid I was driving by and looking at this church like it was something you would see in a movie in Europe, but there’s spirituality in that congregation and also in the Hebrew and Catholic schools down Main Highway. But I think probably because it’s at the north portion, and there’s a huge divide of residential homes, people forget about the Grove also being the epicenter of the most important, more important than Versailles is, the most important cultural destination, and by cultural I don’t mean art I mean the Cuban American culture, for immigrant families in the 70s and to today and I think the Grove has to acknowledge that the same way it should acknowledge Vizcaya right next to it. Even though when most people think of the Grove their stuck in downtown Grove, they don’t think of points north, like Alice Wainwright Park, like Vizcaya, like Mercy Hospital, and especially Our Lady of Charity Church. So that’s, I think, an important connection because it’s so relevant to the majority of people who live in the city of Miami. As you know, the city of Miami gobbled up the Grove, that’s part of the history... of Miami and the Grove. There’s also the importance, the absolute relevance and importance, of the Bahamian village that was created in the West Grove by a gentleman by the name of Mr. Stirrup who was an entrepreneur and who would, literally, build housing. As we think of the Grove and its role in Miami, think of the Bahamian workers who built Vizcaya, they lived there, think of the streets that built Miami, they were there. Think of the first communities of Miami, they were there, and then think of Miami’s incorporation in 1996, again it was a lot of Flagler’s railroad builders, mostly black, who voted to incorporate the city of Miami, so there are lots of clear connections between our early history and the Grove but both communities continued independently because distance is a real thing when you don’t have a car but then eventually they became one and I think that pattern exists today. People who live in the Grove don’t write Miami, Florida they write Coconut Grove, Florida in their correspondences. So that’s sort of like a historic view with a different Cuban exile perspective of what the Grove is but I have many more stories to tell you that don’t focus on buildings, but on processes.

Let me talk to you a little bit about the Coconut Grove Art Festival. So, my dad, for a couple of years, was a teacher at Ransom Everglades, and he taught Spanish there, so I remember as a kid going to Ransom Everglades, which is clearly a part of the Grove, and seeing this school that has the bay for its backyard, and of course it’s an enchanting and beautiful location. My dad also was an emerging artist back then, as was his brother, who exhibited their works locally. These were brand new Cuban immigrants, and they got the local attention of media and other folks who celebrated their work. And I remember their work was exhibited at a gallery in the Grove… at the moment in time when Miami was smaller, it was not at the epicenter of the art world like it is today, they were always excited about exhibiting there. I was very young, I was born in ‘64 and we’re talking the early ‘70s so I was 8 or 9 years old here, but I remember my dad and uncle exhibiting at the Coconut Grove Art Festival back when the Coconut Grove Art Festival was not the actual production it is today with all sorts of security and fencing and tickets and booths and rentals and all that. Back then I remember sitting there with my dad, his easels, his paintings, and you’re just sitting on a chair, there’s no tent, just chilling, and people are walking by and buying your art and that. [There was] a place called the Grove House which is an artist’s space much like you would think of an artist residences or an artist co-op. I remember as a child walking through there and, you know, walking through the Grove at a different speed and, in so many ways, Miami and the Grove had a different speed. The Grove was always a special place, right? It’s not that it was stuck in time, it was that it celebrated its time, it understood its historic role and the people who lived there, I think, because of their proximity to the bay and because development didn’t happen in the Grove the way it happened in open spaces were a builder would come in and take a part of a pinewood rock land that had never been developed or build up a part of a Florida Everglades wetland, fill it, and then put houses on it. Because the Grove didn’t experience that kind of instantaneous development of the ‘50s and ‘60s, or the ‘40s, but instead grew organically where streets had names and not numbers, where buildings were built, not en masse production, but organically through time. It kept its charm and its character, and because development was focused in other areas it allowed it to continue growing as a village of interconnected individuals and a place, an absolute magnet, for artists and cultural individuals.

So, during the ‘70s it was called a place where hippies would hang out right? It’s sort of like a free... I wouldn’t call it fluid necessarily, but you know, I think a place we would all feel very comfortable with where there was this, sort of, artsy atmosphere and a lot of music going around. It always, always had its bars, it always did. Some of which I didn’t, I mean clearly, I [was] 8 years old [at that time] but there was the Eternal Taurus, eternal in name only because of course it got torn down to create a development. The bar is still there and maybe the oak tree that I used to swing a little ring on may still be there, and maybe the front of a bar, but for the most part that memory is gone. Clearly the grand dam of the entire area is the Coconut Grove theater, right? That beautiful building which our Department of Cultural Affairs, at the county level, has been trying so hard to preserve even as times change. The utility of a building built [back] then, the audiences, it’s like a store, a ma-and-pa shop, like the Grove was, trying to stay alive in changing times. Especially as a nonprofit. I think there’s a good plan, in fact I know there’s a good plan, it just has a lot of legal obstacles but once those legal obstacles are closed, I’m confident that in a new shape and keeping some architecturally relevant portions of the building but mostly reconstructed, like the Taurus next store, that this jewel will come back. And [the theater] was an important one, that was an important anchor and its absence locally in the community has created a void in everything from restaurants to the programming that happens on that block; again, asphalt has a way of destroying communities so, you know, the parking lot behind that theater, the necessity to build CocoWalk with huge walls that really are just car storage spaces like a garage, the creation of these massive, completely out-of-scale condos on the northern part of downtown Grove does much to destroy that pedestrian, organic, feel to the neighborhood while giving a nod to the absolute reality that high-density is preferable to urban sprawl, giving a nod to the reality that growth happens and change happens and that nothing is eternal, not even the bars. Their buildings may disappear, and the names stay, and sometimes the names disappear and the buildings stay and an example of that is the Hungry Sailor, which, I have no idea what its named these days, but the Hungry Sailor had live music, it had a Jamaican sort of feel, Caribbean bands would always play there and it was a delightful place for me to go as a high school student. I’m the Miami High class of ‘82, the high school down the street on 27th Avenue and Flagler, and then I went to the University of Miami that fall of ‘82 all the way through 1991 because I obtained three degrees. That decade, the Grove was the destination. It wasn’t until law school, until the late ‘90s that South Beach maybe began to have a scene for bars and parties and that kind of, you know, entertainment, the night life that people were accustomed to in the Grove. So, when you’re a kid in Miami, prior to Woody’s, as in Ron Wood from The Rolling Stones putting the first bar on Miami Beach on Ocean Drive, Miami Beach was irrelevant. You know, it was a place where the movie Scarface was filmed for a reason, right? It was a neighborhood that hadn’t been revitalized yet and there was very little, sort of, entertainment appeal. It’s a place you’d go during the day, hang out at the beautiful beach but if you were in high school or college, so I’m speaking to you from that vantage point, you would always go to the Grove and the Grove was always packed, there was always cars driving around.

Let me talk to you about bars now. I’m glad I started with spirituality and history and civic leadership, let’s go party now!

[ I want to talk] about important places of change in that location. There was this New Orleans type bar that was created, and, in some ways, these things do much to change the character, and I don’t know how successful that was. It didn’t look like it ever succeeded. There was this place called the Village Inn that became a place that looked like a Montana cabin and I used to go eat burgers there all the time, but the Village Inn had a different feel.

So, the Grove... so many memories all over the place. Biscayne Baby’s, the Tavern, Calloway’s, Señor Frog’s, Taurus, and the Village Inn, these are iconic landmarks for me as a kid because I was, you know, getting in there with a fake ID, but was also a place for the adults, like the people in their 20’s, 30’s, and 40’s to also go to. So the Grove was a place where was a place where people would come, its where people who had been traveling would come dock, obviously people who wrecked their ships on our reefs would probably need a little bit more gin than those that were just chilling there, but if you think of it as this oasis, as this place of refuge and escape, you know, if you’re working all day at a downtown bank or at a factory or whatever, going through the Grove was this enclave where, organically, there was a restaurant next to a bar next to a ma-and-pa shop next to a shoe store, so it was a really, really comfortable place to go and there were all these characters. One of the most beloved ones was ‘the healer.’ There was this bald man who gave massages, and he looked wise, he looked like something out of a Led Zeppelin cover, he was almost like a druid, and he was called ‘the healer’ and he would literally give people massages for a buck or two or whatever, and he would use his elbows, he was very skinny. I’m sure he was a master of yoga or something like that but everyone knew him and he would go down and do that and as you would walk up and down the streets there were these characters and activities that were fun but there was also this sort of non-franchised appeal to what the Grove was so that when you walked in a restaurant, it wasn’t a Cheesecake Factory which is what it became, you know? There where interesting restaurants offering all sorts of culinary delights. That of course changes with development but, as a kid growing up, you would go there and it would be a place where kids from all over Miami, Coral Park kids, Miami High kids, Coral Gables kids, all of them, would come together and go to the Grove and you would see that. I mean, most of what you do at the Grove because, again, you are 17, is just walk from place to place and, if your fortunate enough to have a fake ID, you’d get in and after you’re 18, because the drinking age was 18 then, you would get to go to the bars. A bar that we would go to then and also during college was the Village Inn. I remember as a high school kid the Village Inn was a primary destination because it played live rock so it was a bar but there was a stage to the right. It had two doors and, to get into the concert area, there was always a line and a bouncer at the door, and it would have great live music and I remember when that closed down everyone lamented it because it was really a place making locale for people. Drinks were pretty cheap, and they had all sorts of cool specials, but it was a really, really good venue. Then it was turned into a place that harkened to one of these cottages in the west, you know, one of these ranches in the west were huge stones were imported and big thick logs and all sorts of dead animal skins everywhere, like a lodge. So that changed it a little bit, you know, it’s trying to take the beauty and greatness of the Grove and do what you do to a golden goose, you open it to get more eggs and you find that what really mattered was the intimate, smoky, dilapidated bathroom and rooms of the Village Inn and all these other spaces. You build these big castles for it, and then all the sudden the public doesn’t come, you don’t have that feel. The same thing happened just down the block there after another developer came in and built a party hall, but this party hall looked like it belonged on bourbon street, right? So one looked like it belonged in Montana and then you walk a few blocks and instead of being to scale, this was a huge building with the most ornate iron work and stained glass and it felt like a mansion, it had all these trappings of luxury but totally out of place and out of scale and, you know, I don’t know if they survived, but for the longest time it was always empty, like nothing ever happened there. Across the street from that I remember as a kid going to a movie theater, it was another building... or simply just one-story retail spaces that had over time taken over what I’m sure were wooden houses or groceries, or whatever Miami’s historic scene was in the 1920s and ‘30s. Someone came in and raised those and created these one-story retail spaces. Many of those spaces still populate the Grove but, over time, they became familiar. But in came the developers who popped in CocoWalk, popped in this place, I think the cinematheque, which was in this white concrete space that was all angular and had a modernist look to it. The place where Calloway Jacks was, which was like this open-air bar, now had a Johnny Rocket’s anchoring it instead of, you know, sort of, a more commercial sort of feel to it. And, like it, places and spaces across the Grove changed. I haven’t touched the Mayfair, it also had bars inside of it, I can’t remember their names, but all I know is that when I went there with my high school buddies, they didn’t care about the fake IDs too much. I know now that it was surrounded by drugs and crime and that it was like a real bad place for a 17-year-old to be in, and the drinks were super, stupid expensive, you know, like “what the hell? Five dollars for a drink”?

Ashlye Valines: It’s funny you should mention that because one of the bars I was researching “Faces in the Grove” was in the Mayfair, and that was owned by a man who was shortly after the 80’s, unfortunately murdered in his home by a drug dealer.

Xavier Cortada: Right. That’s exactly right. It’s Faces, that is the bar. And then the Mutiny Hotel had its own bars and all that stuff. Look, I’m painting a picture of the Grove in the ‘70s, which is sort of more of a hippie culture, for lack of a better word, flower power kind of place, but there’s always been wealth in the Grove, but it’s a different kind of wealth. Miami really was in a bad place in the 1980s. The drug wars in Colombia were now spilling over to our streets. Castro’s prisons, and not political prisoners but criminals were now, literally, in the streets of Miami living under a tent on the Miami River, alongside the other 90,000 of 100,000 people who were honest Cubans fleeing a regime that took everything from them, and their kids were with me at Miami High. That’s what Miami High was, that’s where Mariel children came. And, at the same time police officers murdered McDuffie, literally murdered an insurance agent on a motorcycle named McDuffie a la Rodney King, beat him to death, and an all-white jury in Tampa acquitted the cops and had Liberty City burned. That is 1980s Miami, and it is a place drug lords became really comfortable using machine guns to kill cops and to kill people at large and they would, in many ways, own the streets, so yeah, again, I wasn’t oblivious to Mariel or Liberty City. I kind of new about the drug lords because Miami was the murder capital at that point, 800, 900 deaths, but at the time, I had no idea that Faces, well, I guess I did, like “oh, okay there’s drug dealers here” but what does that mean for a 17-year-old? The point is that, right then and there, you were seeing these transitions happen, you know, they weren’t at the Hungry Sailor, they weren’t at the place where you wear jeans, they were at the place where you had to dress up in your polyester clothes and that’s what those bars were signaling towards.

Over time the Grove continued its changes. I remember spending so many wonderful times at a place called Señor Frog’s, the site of the current burger place, Johnny Rocket’s, and what I loved about that bar, again it’s at that magical intersection you know, facing CocoWalk, but there was a big window, and the bar was in front of the window and it was a restaurant, a Mexican restaurant, but this little bar by the window was a place where my buddies, Andy and I, and a bunch of Lambda Chi, would just go to that location. When Señor Frog’s closed they opened on the other side near Coconut Grove theater next to a restaurant that, my god, how could I not mention? If there’s a restaurant that’s been there eternally it’s the one next to Señor Frog’s, Greenstreet Café across the street from the Village Inn. So, Greenstreet is this iconic restaurant. Why? Because its open air. So, before there was the Lincoln Road outdoor eating thing, you would go to Greenstreet, you would sort of sit there and you would eat, and Greenstreet is another fabulous location. Again, not the kind of place a high schooler goes to eat.

There was another building, Fuddruckers was a restaurant, I think it closed, again another commercial restaurant like Cheesecake Factory, on Main Highway that literally created this tall building and again, more displacement happened there. They tried to create some courtyards and stuff like that for it to work but something happened with its design, something happened with the CocoWalk design, where the retail spaces just weren’t attractive. What worked was the new model, the big Cheesecake Factory and the movie theater, but this whole idea of a place where ma-and-pa shops would work now has stores like The Gap and huge franchises that really sucked all the oxygen out of it. It was just a regular mall but inside had a faux fabricated structure to look like Montana, New Orleans, or the Mediterranean, instead of having that old Grove feel. And again, this is a conversation for planners, it is the way of development, it is what happens, but I’m glad that exhibits like yours allow us to celebrate that moment of what once was so that we can reminisce and think about it and, I think what’s most important about an exhibit like that is that it lets us chart a course for the future, so that as we sit here today and unravel whatever we have come up with now, we can understand the consequences of that as we continue to scale up and build up. And we have to. We have to adapt to new technologies and new ways of living but there is always this consequence and once you destroy the character of something it’s impossible to bring it back, so that inner network of people that lived there and worked there and interacted there and played there has forever disappeared and now there are new layers that are built on it.

As an 8 year old, I remember I grew up in a house that was mostly monolinguistic, we’d all speak in Spanish at home, and we would buy our cold cuts from a Cuban grocery so we would have jamón and jamón cerrado but not so much bologna and salami, so I remember that on the corner of where Sharky’s is, and Sharky’s was across from the Greenstreet Café… Sharky’s was a popular eatery, vintage 1980’s, people would eat outside, it’s a cafe and I remember those brick like cellphones at the beginning of the cell phone era that people would show off, and it was like the size of a brick and you would speak into it. So, I just have these memories, because a lot of the times we would just go to the Grove to chill and seeing those brick phones in front of Sharky’s, and Sharky’s was a restaurant with a Miami Vice flair. So it had the font of the logo and the colors of the menu that were very much Miami Vicey, so at that time it was that but I remember that very same location was a deli, was a grocery store, and my dad had an exhibition across the street with his easels and he and one of his friends from Ransom went there but, of course because my dad worked there, he was familiar to the person serving the sandwiches. So, I remember this, sort of, butcher guy in the back talking to me saying, “which sandwich do you want? Do you want a bologna, or do you want a salami?” And in my head, I didn’t know which of the two I wanted because they were unusual to me but I wanted the one that had the most meat on it so I’m thinking I’m gonna have a big Cuban sandwich and, you know, a bologna sandwich is just 2 pieces of bread and a slice of bologna. So the point is, that kind of charm where a butcher can just know who your dad is and talk to you about what you want and he serves it for you, you know, you’re not reading it from a Miami Vice colored menu, it just had a different sort of feel and not only did the Grove change, but I changed too, like ten years later I was walking into that same place and ordering from the Miami Vice menu and was really comfortable ordering conch fritters or whatever. So that’s one reality that the Grove had.

The Grove also had a gay history. I came out later in life and I am not as privy to it but I know that as college students we went to this place called the Tavern, which is sort of close to where Main meets Grand, you know closer to the CocoWalk area but on the side, in fact, there’s a building that you could walk all the way through, right now there’s a French restaurant, maybe a smoke shop and then next to it is where the Tavern was because it closed down, but for the longest time the Tavern was a real big destination for University of Miami students and what we loved about it is that they took pictures of us and the walls of the Tavern were covered with our photographs like, literally, everywhere. Those photos were iconic because, years later, a decade after we graduated, my fraternity brother would come to town and we’d go for a drink and, of course we had to go to the Tavern and there’s our little picture there. So, that bar, at least by recording the people, had that feel, that sense of community. Again, different world different people, mostly non-Miami, U of M kids who lived in New Jersey who would spend 4 years in Miami, but still it had that certain charm and feel.

For a minute, I was attending St. Stephens as a parishioner and, again, not the same St. Stephens that I’m sure was there decades before, but still there was a sense of community in that location. I’m sure that the PTA and the parents of that school not all lived in the Grove, but still had that sense of community and connection through St. Stephens. Monty Trainor, and his team at Coconut Grove Art Festival now inhabit a place at the Mayfair and tried putting a gallery there that has had some success but, again. because we have barricaded natural ways, it’s a big wall, the Mayfair is a big wall, and there’s very little foot traffic and the areas above it have been converted into office spaces. People would come in, inhabit an office, and leave, so there’s a lot of loss, if you will, of that sort of granular interaction. But Monty has tried to keep it alive since he became the director of the Coconut Grove Arts Festival by invigorating it with this annual, it think it’s one of the largest, very well-known art festival that brings culture to our city and I think that’s sort of another glue or fabric that keeps it together. He invites a lot of local groups from our Dade-County school teachers to exhibit kids work, like kids from New World’s School of the Arts.

There are some things that are lost forever like Biscayne Baby’s which was this night club just of off Virginia Street in the Grove, right behind CocoWalk. I think by the time South Beach became a destination in the mid-90s and to today, these big, huge, mega bars started losing their appeal. And of course, South Beach is no longer cool, well, maybe it is for spring breakers, but it stopped being cool a while ago, and then Wynwood became the new space. So, I don’t know anything about the excitement that you saw in South Beach in the ‘90s and 2000s or the excitement that we’ve seen in Wynwood in the last decade but if you lived those moments, and you understand how communities come together and enterprises and cultures and individuals and characters organically pop up in the scene, well that’s what the Grove was. The Grove was the precursor to the South Beach and the precursor to the Wynwood that we have today. I think the architecture has really done much to harm that and I’m not sure what the Grove will come to be, I know that the Grove has bigger problems then not having kids partying in their streets. It has other visitors, and, in this case, the visitors are sea level rise and that will hit them first. There’s a good portion of the Grove that sits on a ridge, so that’s healthy, but, you know, all the other areas, our beloved Miami City Hall is at Dinner Key in the Grove. I’m sure you’ll talk a lot about Dinner Key and its importance in Latin America and its sea planes. It really helped put Miami on the map with its flights to Cuba and back. There’s an entire community of boaters living, literally, on the water that’s also an important story.

I think an important story is all the schools down Main Highway. They are like real living communities. With St. Stephens and the Hare Krishna temple that’s still just a little further north of that Italian restaurant. I remember me and my friends lived in something that looked like Melrose Place the sitcom. They lived in this gated, eight-unit apartment, and I remember always going there, hanging out with them, then going into the Grove, hanging out at night, then crashing on their couch or something, so the Grove was that. The Grove was also a place where friends would go, from a residential point of view they had this tight knit community still there, they are residents that I think have the strongest sense of community and bonding. I think particularly so in that area in downtown Grove because you don’t live in spaced-out houses, but there’s a dog park and a sense of community. In fact, our commissioners that cover the entire seashore are civic leaders that became political leaders because of their role. I think another danger the Grove has besides sea level rise and the impacts of climate is the gentrification that’s happening with the West Grove and what that means to the people who, for generations, have built community there. I saw a Walgreens pop up across from the current post office back when that was the venue for the Rocky Horror Picture Show. That was magical, sometimes you would see concerts there. I saw Led Zeppelin documentaries there, but Rocky Horror Picture Show at that cinema was legendary. So, you had the cinematheque, you had the national films, you had the Rocky Horror Picture Show always happening there. You had your drinks at the Village Inn, you had a community where you could walk around. So, it was this really awesome destination. So that’s the heart of the Grove there. The gentrification of the West Grove up Grand Avenue will continue to be a problem and for the same reason they have these Grove houses that they called shotgun houses that are disappearing because these are simple structures, literally you called them shotgun houses because you open the front door and shoot your shotgun straight through and it’ll go out the back door. You know very simple rudimentary homes, but they sit on extremely valuable property. There’s also a community of faith leaders, there’s cemeteries, there’s all sorts of culture there that is disappearing. I also think I want to take you to the Miami Science Museum. For the longest time the Miami Science Museum, before it moved to downtown Miami, lived in the space that were basically the farm and garden space for Vizcaya, but it had Bayshore Drive on the right and US 1 on the left. And it was an important location because it was tied to that downtown area. It feels like it’s not part of the Grove, but I want to acknowledge that it was literally part of the Grove and an essential component of it. And US 1 completely change the character of that. Asphalt and concrete do so much to erase but that, I think, is an important place I’d like to mention.

I want to talk about Monty Trainor’s’ place right now. You know it as this two-story mall. I think there’s a Starbucks there and then there’s a restaurant that’s in the back and it’s an open restaurant with tiki huts. It’s nice, it’s actually a nice view than what we used to have. When we finished, in the magical ‘80s, winning a championship game at the Orange Bowl, another thing that has disappeared, we would all go to this place called Monty Trainor’s and it was a square, one-story building at the corner of Bayshore, right now it’s an asphalt lot but I just want you to know that it was an absolute destination and an eating place and a bar and all that. And it was so good that now it’s franchised in another one of these two-story malls in South Beach. And things happen in society, but all these franchises come from places that were organically created and had a sense of community around them. So, when you go to that parking lot you don’t have the same feel that you had in the ‘80s when you went there. Next to the Coconut Grove parking lot you have that airplane hangar. I know that hangar well because I painted an airplane in that hangar in 2004 when the US Marshals took it over when a plane was stolen from the Cuban government by a family looking for freedom who bought it to the US. That hangar is currently used by a local nonprofit that teaches kids with disabilities how to sail and that is a good purpose for that place. Next to it you had the Chart House, which was an elegant place to go I think, that and a new farmers market that has been developed has changed it a little bit. And a gem of the Grove that was next to City Hall which has disappeared is a restaurant that was literally inside the marina, Scotty’s Landing, we went there all the time for the fish sandwiches, and it was next to the Chart House.

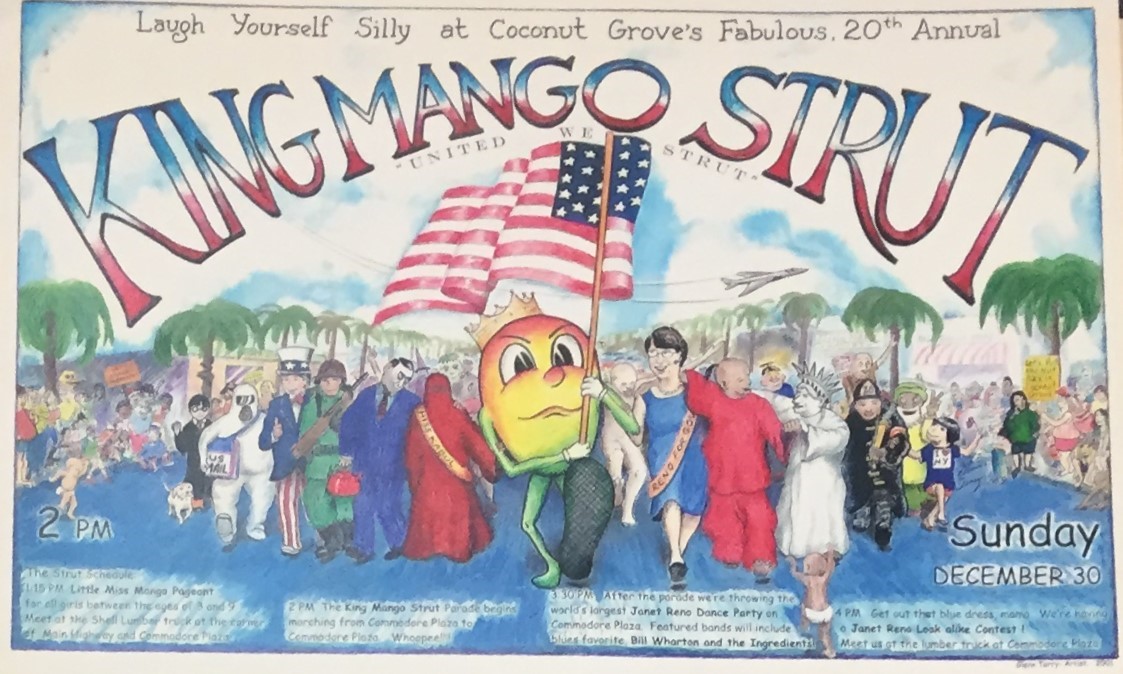

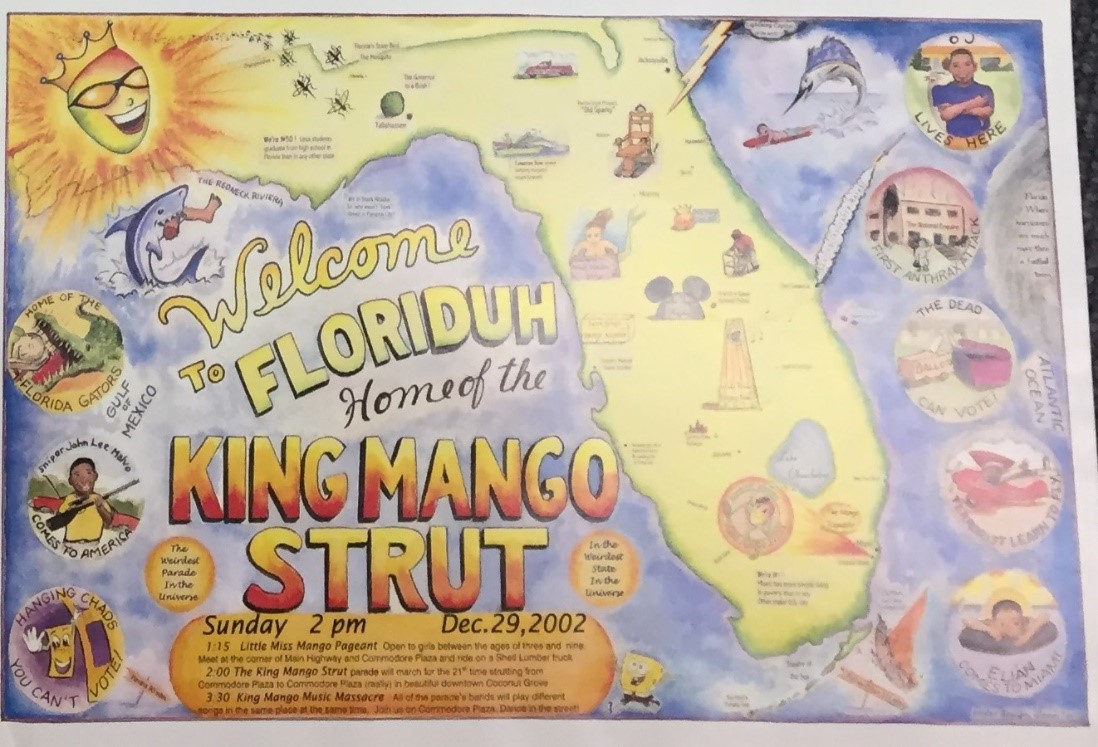

Scotty’s Landing was awesome because it was the only place that gave you that kind of proximity to dining on the water, but it wasn’t really dining. The stuff was served in a plastic bag. Their conch chowder was served, I think for the longest time, in Styrofoam. It’s not elegant. There was Ketchup bottles on the table and there were all sorts of birds, literally, coming and eating the breadcrumbs we left. But it’s magical because the Chart House next door faces inward, they had a view of the bay behind glass, most of it covered, and there was the Rusty Pelican which, again, you’re indoors on the second story over on Virginia Key, but here at Scotty’s Landing you literally had to jump over a chain to get in. You had to run your way through the big tractors that would pull the boats out of the water and collect them on shelves. You had to compete with the smell of oil in the gas pumps that were there fueling the boats. And it was always very chaotic and there was always a line but that was a real magical destination. And what was so good about it was that you knew that it was a local place. It was off the beaten path and you literally had to watch out for these huge machines that were hauling Boats in several times and cross over a greasy, smelly, almost toxic, floor to get to this place under a tent to order your grouper fish sandwich and there was something really, really delightful about that and sadly that is gone because some developer wanted to take the Monty’s model and slice that golden goose open and create something different. I don’t know exactly what that’s going to be. It will be an outdoor restaurant that’s facing the water but that feel is lost. It’s like taking something that was good and trying to make it better but actually ruining it and I think that that’s what I want to say about the Grove is that it’s kind of done that. They are trying to explain what happened naturally but by scaling it up and monetizing it more you actually destroy it. And the reason that happens is because a firm or developer that’s not close to the ground and doesn’t have the same feel for community because they’re not part of it and are just imposing their brand doesn’t resonate with that. And they’ve created a series of structures that don’t work. CocoWalk is the most obvious example of something that didn’t work. It worked for the movie theater and, look, it was the closest movie theater to my house, and I have watched every major movie in that place, you know? I’m not trying to diss it and I drink at the café and I did visit Cheesecake Factory but, as a growth, as a place where community comes together with bookstores and the kind of stuff that would normally survive, that kind of a village disappeared. There needs to be a better approach, and this happens through government, this happens through zoning, this happens through the will of people who can convey their ideas. There’s got to be a better way of protecting these jewels so that transition happens but in a more ordered way. What happens is many lose, starting with the very developers who came to profit from it… but I think I would rather say that our community lost most because that’s not coming back and that’s what we’d like to limit. We could have the same argument about downtown Miami and what happened to it and how it’s having to try to have its revival now and I think the Grove will but I don’t think it’s going to be anywhere near what it could’ve been. The Coconut Grove Playhouse, the Coconut Grove Arts Festival and some organized and culturally sustained programs from the West Grove like the Goombay Festival and the King Mango Strut Festival are wonderful but they are just temporal. If there’s a way of bringing that back I think it would be great for the Grove. I’m trying to do justice to the parts of the Grove that I care about and know about, but I have completely ignored South Grove. The reason that happens is because absent these places and making communal spaces, they’re just private locations with their own histories. But the beautiful thing about South Grove and a lot of the Grove is that its lush so what you see is just jungle. But you don’t really understand the fabric of the South Grove community unless you’re in there. I’d like to shout out the Kampong as a really, really, relevant jewel of the South Grove, where Dr. Fairchild, literally, lived and had his lab. So that is a beautiful piece of the South Grove that’s relevant to me.

As you go up the Grove it’s important to acknowledge all those educational institutions. Those institutions have given up their land, their beautiful acreage to make way for big mansions. We know that the spaces that were forested have given way to developers to build homes, like the homes that were built across the road from Sharky’s on Main Highway. And more is in danger right now. I am a little bit worried about the northernmost point of Coconut Grove, Alice Wainwright Park.

For years because, you know you cannot always get into bars but, 7-Eleven lets you buy MD 20/20 and then you do what you do as a 16 and 17-year-old who shouldn’t be doing that, and then you go and howl at the moon by figuring out how to break into a bayfront bar. I remember going through the Hardwood Hammocks with my friends and then taking my college friends later there to the northernmost point of the Grove and just enjoying it. And for the longest time those Hardwood Hammocks had been preserved. They were actually fenced off in the main entrance to the park. So, you go and just cut through the Hammocks and you see parts of the ridge there, you see the bay, it was barricaded with the seawall, but you could see the bay. You look to the right you could see Vizcaya. Rocky or Madonna used to live on that street, it’s a really posh place. There was a lobbyist who tried to close down the bike path there. I used to live across US 1 from that so I would literally walk, or get on my bike, walk to Alice Wainwright and then up Rickenbacker and back, but the lobbyist had Rocky or Madonna, one of those people, hire her and they wanted to close the small little gate that connected that street to Key Biscayne and the Rickenbacker Causeway because they didn’t want people like us to be on that street, but the city of Miami looks like it’s planning to make that park more available to people and I have nothing against it. I think we have we should have more parks. I am lamenting that parks are becoming homeowners’ associations where homes are built between whatever trees they weren’t allowed to cut down. But I’m afraid when they say that they want to open the Hardwood Hammock so more people can enjoy it, what they mean is the very little remaining Hardwood Hammock on the bay so that we could put ecological experiences for folks. For instance, Simpson Park outside of the Grove, much like Vizcaya and Hardwood Hammock, have to be protected and if we can’t save the buildings that are gone at the very least we need to save the very little ecosystem that’s there and that’s what I think is important about that particular part of the North Grove.

My dad’s favorite house was on the corner of 17th and Bayshore. We would have to turn left there. We lived in Allapattah, we would come up 17th Avenue or 22nd and 17th, we would take that road all the way down, make a left to go to La Ermita and, my dad and mom were very religious so it was literally every night, we went to Catholic school all day, then we went to a Catholic daycare center at night, so you spend all day with the nuns then you go to daycare with more nuns and then you go home, but then at seven we go listen to mass at La Ermita. Each of us had our favorite home and I remember mine being this big place and there was a white house in the back but what I loved about it was that the ridge was really exposed and looked almost like a cliff. There was this front lawn to this house, except it actually was the backyard, but each of us had a home and they were these really beautiful mansions.

I think that the community and the people who live there I think that is as intact as we can get in a society where there’s more divide. I think there’s still a good sense of community and neighbors interacting with neighbors. I’ve seen that in my friend’s neighborhoods but it’s these other place-making spaces that I think are in peril.

Thanks for honoring me by giving me an opportunity to share a little bit of my history with a place that, as a child, my dad would take me. It’s a place my dad introduced me to as opposed to my friends, and it’s a place that I could then showcase because I knew it so intimately, to my high school friends. I was the resident expert by the time I am taking my out-of-town U of M buddies, and it’s a place that has honored me. I was a Coconut Grove Art Festival artist in 2008 and it was fun to be there. I depicted mangroves, the same mangroves at the end of Peacock Park, as a way of launching my reclamation project which I launched at the Bass Museum but brought to the old Science Museum in Coconut Grove.

Ashlye Valines: Thank you so much, Xavier. This was incredibly insightful.

- Don Deresz

In 2004, a call went out from the newly remodeled Mutiny Hotel in Coconut Grove for writers to submit short fiction stories to help promote the grand reopening of the hotel. Please enjoy the winning story and a short interview from the author, Don Deresz.

Amy Galpin- Where were you born and when did you move to Coconut Grove?

Don Deresz- I left Detroit for a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker exploring both Poles as a hospital corpsman in 1966, then finished college and went on vacation to visit my brother, Bob, in Coconut Grove in 1973. I've been on vacation every day ever since.

Amy Galpin- What are some of your favorite things about Coconut Grove?

Don Deresz- From the Grove, you can sail to, and appreciate, all that this world has to offer. When in homeport, you can enjoy the creative artistic, literary, and performing talents of people who also made Coconut Grove their home or were just visiting. There were superb cafes, bistros, and restaurants with outdoor tropical settings serving delicious meals with local fruits and veggies, and even "sweetbreads" that tantalized all of one's senses. Fresh fish on the hibachi could be a daily moist and spicy delight. One could safely bicycle or walk everywhere,

while sighting migratory birds and the seasonal kaleidoscopes of butterflies making their way down Main Highway, with a nightly fragrance of jasmine blooms piercing the air.

Amy Galpin- What are some other memories you have of Coconut Grove?

Don Deresz- Devouring and slurping on mangoes while standing in a bathtub. Skinny-dipping in the Miami moonlight in the Coconut Grove Hotel swimming pool with a dark rum in a glass with a little water, and a wedge of Key Lime.

Amy Galpin- Does nature play a role in your desire to live in Coconut Grove? How has the natural environment of the Grove shaped your experience of it?

Don Deresz- I met Gretchen on a boat, and we sailed and raced near and afar. We lived in a one bedroom, rented bungalow hidden amongst our tropical forest on Virginia Street, with brick paths, a pond, and an outdoor table to make our own fresh kielbasa. Gretchen taught me about tropical plants and an appreciation of art. She has enhanced my life. The condo craze created by the laundering of drug smuggling money beginning in the latter '70's, forced our evacuation to a residence just "across the tracks" within a short walk to Kennedy Park on Biscayne Bay. My studies and work as a teacher brought me to a greater understanding of marine ecology.

Being proactive, in concert with fellow Miami neighbors, to improve our natural environment and quality of living, requires constant vigilance and political finesse to influence and bring awareness to predisposed City and County Commissioners.

Amy Galpin- We are excited to share your written work with our audiences. Do you write often?

Don Deresz- Although published, I am not a professional writer, but my career as a Miami-Dade County Public School teacher required certain writing skills that enhanced my income creating curriculum materials. Also, the advent of online academic websites in the latter '90's to post university course assignments and such, which were not only read by professors, but also peer-reviewed by literally hundreds of students, satisfied my mid-life need to write “my epic.”

Funny thing—it's certainly a small world as Mr. Glen Terry phoned me at my worksite many decades ago to inquire about my thoughts regarding entering the teaching field. I warned him, but he didn't listen and took the successful plunge as a career.

Please accept my offer of "A Pirate's Lair," a historical depiction of a hotel in Coconut Grove during the '70's. This piece was entered in a promotional contest to re-open a remodeled Mutiny Hotel in 2004-05.

Entries were submitted by professional writers from around the nation. Much to my surprise this amateur won, which provided my wife and I with an enjoyable weekend in their spankin' new penthouse.

As a further goof, I arrived at the grand opening, evening ceremonies dressed as a pirate to keep my identity a secret for professional purposes. The piece was fiction, but the vignettes were based on Coconut Grove characters that I met over the years.

Incidentally, it was a real hoot to wander through this FIU exhibit and meet old Groveites, who I had never met before; but we were thrilled to share memories.

- Lilia Garcia

In this interview with Lilia Garcia, Director/Curator of the Coconut Grove Arts Festival Gallery, conducted by the Frost Museum’s Assistant Registrar, Yady Rivero in April 2021, we learn about Lilia’s unique relationship to the Grove and the rich path that led her to her current role as director and curator.

Yady Rivero: My first question is, of course, about the Coconut Grove Arts Festival. How did you become involved?

Lilia Garcia: Let me give you a little background on me first. I was an art teacher. I got a master’s degree from FIU. I got my undergraduate’s [degree] in UM, and a specialist from NOVA in Leadership. So, after I graduated from college, I became an art teacher.

During that stage, this principal calls me up – he was the principal of Coconut Grove Elementary and he said, “I’m on the board of the Coconut Grove Arts Festival that’s 30 years old”, something like that. He asked me to join the board because he wanted me to start a program with the Coconut Grove Arts Festival. He said “We have all these artists come in, for 3 days. Some stay longer or come earlier because they have to do all this set up. And sometimes they stay later for shows. I want to take them to the schools.” So, I say, “Fine! But what is a board?” and he said “Well, you have to come to all the meetings…” And I said, “That doesn’t sound bad, I live nearby. But I want more than just the program. I want money.” “Money? But none of us get paid?!” “I want a scholarship fund.” And he said “Oh that’s a great idea! Let’s work on that.” So, I joined the board that year.

The first program we started was the Visiting Artist Program. Where I would ask, of the 200-300 artists, how many would devote one day of their stay in Miami to visit a school. And they could choose what grade level and if they wanted a high school – 2d or 3d. I had sculptors, textile artists, ceramic artists. The first year I had around twenty participate. Today we have around 150. And now it’s both public and private schools. And some artists come days before and they don’t do just one school, they do two or three. Especially minority artists. A lot of artists are very shy, so I got an art teacher to go with them until they felt comfortable. And the teachers started calling the artists back “Oh, you gotta come back! You were so good!” And I had a few artists tell me I had changed their lives because from there, they wanted to teach. Every year I had someone say, “Oh my God, I didn’t know it’d be so much fun!”

So that’s how I started in the board, it was the mid 80’s. The board was small at the time. It was mainly men— it’s still mainly men. And the majority of them were lawyers – people who needed this type of community service on their resume. I didn’t need it. Nobody knew I was doing this in the school system. They just knew I did everything. I started a program with free tickets so I called every cultural center in Miami and said, “If you can’t fill up your program, give me your tickets and I’ll give them away.” One year I gave away 5,000 tickets. I wanted teachers to have access to them. Because with teachers—most teachers are not cultural, they’re blue-collar workers.

The principal who brought me in, his name was Dr. Von BB. He was not your typical principal. He was always thinking about the family component. We were always conscious about giving parents tickets to the Festival. Even today we have a discount ticket program for Grove residents. With him and me on the board and with a few others that came in when I did, they realized that – even though the festival was running fine – we needed to do more community-based things. And my perception always was that if we wanted to be a strong component of the arts in our county, we couldn’t just be a 3-day event. We had to be ongoing. We had to be a year-round organization so we could provide activities throughout the year. And kids were the easiest things for me to do. So that’s what we started doing. The scholarship program came about easy. The first year was $5,000. Now it’s $25,000 every year. We give them an art show and we do a training for them. There’s an organization of retired art teachers that work closely with us in preparing the kids. So, by the time we give them the stipend, it’s to recognize them. High school seniors. And now they’re artists.

The beauty of what I do with the CGAF is, I’m retired from the school system, so now it’s allowing me to give back to those kids who were very interested in the arts, who went through the system, and are now emerging artists. So that’s how the gallery came about. They had this beautiful space that included a pop-up near the front, right on the sidewalk. And I opened it the first year that Basel opened here in Miami. And I did it with kids form New World School of the Arts that had just graduated. We had 6,000 people come through the gallery. They told me I could have this gallery for 6 months.

My husband, who died 5 years ago, was the founding art teacher at New World. He started a program at the gallery, that we still do, which is to give New World a free booth, and they give one student artist the experience of what it is to be a selling artist. They have to create at least one painting and it has to be something about Miami. And the kid was responsible for everything. Bacardi was a sponsor, and they’d donate mats. And the kids would have 2 hour shifts at the booth, and they sold the pieces for $100. The students would keep half. They sold $30,000 worth of art. They had to do inventory, they had to watch the booth, count the money, represent themselves, everything. Sometimes teachers from New World would get upset because the work would sell so fast, so now they do a presale.

… I also recruit artists by traveling to different fairs across the region and country.

Yady Rivero: So, let me ask you about Coconut Grove specifically – were you raised here, or did you move here as an adult?

Lilia Garcia: I don’t live here. I live in the Gables. Three minutes away on LeJeune, where Merrie Christmas Park is. I moved around.

Yady Rivero: What has been your impression of Coconut Grove throughout the years?

LG: When I was a kid, Coconut Grove was something special. I would never think of living there, you know I was a refugee little girl. But it was always fun. We drove around it and through it. I don’t think we often stopped in the Grove. Now, I went to UM on a scholarship. And of course, all the kids wanted to go to the festival. The boys to pick up girls and the girls to get picked up. I remember coming in with friends, and the boys would drive around Grand Avenue for hours! Honking their horns, it was the thing to do! And I would say, “Boy, what are those boys looking for!” Even a few years later when I was in my twenties, they’d still be doing it. For a long time, it was the thing to do in the Grove. So, I would come to the Grove when I wanted to be cool.

Yady Rivero: Were there bars you liked or music venues?

Lilia Garcia: When disco came on, I loved to dance. Discos here, you know places to dance, the one I liked most was right here, it was called Ginger Man. It was owned by Monty [Trainor] who is the director of this place. It was a private club so men that were there were higher-ups. And the women could get in without paying, without being members. So that was a lot of fun. And then my other favorite was Regine’s, in one of the hotels. That one was owned by a French woman. And, they had happy hour with free food! And me, I would go anywhere. I’d go to Coral Gables; I’d go to Fort Lauderdale. But Coconut Grove was the place to go. I don’t think there was a nightclub here that I didn’t go to.

Yady Rivero: Would you say that prior to joining the CGAF, you were interested in a lot of the art spaces here?

Lilia Garcia: Oh yeah! I’m an artist! Look at what I did this morning! [Ink doodle on tablet cover]. I went into education for survival because I knew I wasn’t good enough to be a well-paid artist. I have a background as a commercial artist, and I hated it. I didn’t like the atmosphere. I still do a lot of marketing though, because life is marketing. I used to tell my old teachers this, that if you’re in the arts, you have to toot your own horn. You need to say “I’ve done this! I’ve done that!”

Yady Rivero: Especially as women.

Lilia Garcia: Yes. And I’ve done the research. If you look at administrative positions in the arts, you see that as you go up, there are less and less women.

Yady Rivero: I know that you’re a Board member of Oolite Arts Miami. I’m curious to know what you’d say the state of the arts are today.

Lilia Garcia: Coming from my background when there was so little. There were maybe 2 or 3 art galleries here, and they were only for a particular few. I have seen it grow beautifully. The talent has always been here, but the talent has become stronger. And I think one of the reasons is that the make-up of this community is from so many different places and coming from so many different strata of income and all that. It’s like a pool of great art – and one feeds the other. I know that in most schools you have kids who hate each other. It’s like, “Oh, this is a black kid” or “Oh, this is a Hispanic kid who just came over. I don’t want to sit with him.” In an art class, you don’t see that. In an art class, kids are just looking to see what work you’re doing. And if you’re good, who cares what color you are? They want to see what you’re doing! I see that and it’s exciting to me. I had a kid in my class who was legally blind, and the other kids would come and say, “Oh my God!” Nobody would talk to him – he was very tall and black. But when he started painting, kids would come from everywhere and ask for him, they wanted to see his work.

Art is expanding. Art used to just be painting and sculpture. Now it’s everything! Now it’s illumination and sound and projection and ceramics. So, what I’m working on, for the future of CGAF is installations. I want to bring large installations. Like music festivals, like Coachella or Burning Man. We are also working very closely with the Chamber of Commerce, since there’s more interest in working cooperatively. We are working with BID and the Women’s Club. We want it to look beautiful so it’s very high cost. We also hire private security. I am responsible for the jurying and the judging. We have a blind jury, that evaluates the work of artists who apply. We use ZAP, the online platform for people to submit their work. We judge it here in this room, at this table. We use 5 monitors. We get around 1,000 applicants for the festival and we choose around 380 artists. I like to do this part together in the same room.

Yady Rivero: The jury is comprised of artists…?

Lilia Garcia: The jury is artists, curators, university professors. Each year is different. $50,000 of our budget goes towards awards.

Yady Rivero: Do you make an effort to get diversity candidates?

Lilia Garcia: No, it’s whoever. I don’t know if that’s right or wrong. We have artists of different backgrounds. I do share application deadlines to Black artists through the Black guilds.

Yady Rivero: To wrap up – you know, this exhibition is essentially providing an art historical narrative for this area of Miami. I wanted to know what you think about the importance of that. Not just for this exhibition, but in general.

Lilia Garcia: Telling Miami art history is so important. First of all, I think it’s so important to tell every history. And a lot of this stuff we know as history is a lot of rumors that actually didn’t happen. I’ve been listening to this podcast on a study they did about being Black, and it hurt me for a while to even listen to it. The history that I was taught – there’s so many nuances within that history that aren’t taught. It was shocking to me. So, the same thing is the case with the arts. History is important because of that. Those little stories… especially for a community like ours that is so fragmented. It’s hopeful for some kids to see. Like, “Hey, look! This guy made it. This Gene Tinnie gut.” Gene Tinnie and I go back many years.

Yady Rivero: That’s great! I’ve seen his work. I’m a registrar so I help with the loans and it’s great to hear stories about the person behind the art, since registration is very object focused. But now I am getting a picture of the artist.

Lilia Garcia: Gene’s background is Foreign Languages. And he traveled a lot. He interned for me. There was a special program for people in Miami interested in the arts. They would take them and put them in different places to experience the art world. And Gene Tinnie was with me for six weeks. And he loved teaching. He’s very calm and wise. I love being around him. Everyone thinks he was a basketball player, but he never played sports.

So those connections are important to keep. Because if you don’t write them down, if you don’t show them, they’re lost.

Yady Rivero: That’s great, and you mentioned earlier you wanted to start a curatorial program?

Lilia Garcia: Yes! Three major projects. One is my baby – called Oolite Wheels. Which is a revamped truck so it’s going to be a maker’s space for artists with a 3D printer and other technology. It will be completely equipped for artists. On the back it will open up and there will be a screen for showing films so people can sit in the back. It will have a gallery inside. We can take a whole art program and bring it around town. We’re thinking of bringing it to Homestead, Doral, Opa-Locka, those communities.

Yady Rivero: Oh, that’s great. Bringing it to the suburbs.

Lilia Garcia: Yes, we can also rent it out. The first thing is to buy the bus.

The second project is a journal about art in Miami. And we’ll start with coverage about artists at Oolite and we’ll try to get the New York Times and the Chicago Times to run the articles. It will be virtual, but we will have an editor. The idea is to boost our artists.

Th third project is a kit, a skills kit for curators. Each day do a different research category on how to put up a show, how to do artists visits, all that kind of stuff.

Yady Rivero: And that would be for college students or high school?

Lilia Garcia: It would be for whoever wants it. Mainly artists who want experience with curating or young curators who want to up their skill.

Oolite actually started at Coconut Grove. Which is kind of interesting. Nobody knows that because they don’t have the history I do! But Oolite – there was a place in the Grove and then later where Johnny Rocket’s used to be. It was a place to do art. It was full of artists and classes for adults. And if you wanted to try something new, it was a community for artists. And I went when I was at UMiami because I was interested. I met this woman there whose name was Eli Schneiderman and she was working – she was a psychologist at UM who took a class there on ceramics and loved it. She took classes with Juanita May who was a master ceramicist. And then the place where the Grove House was located was sold.

They sold that space and then they moved to the Johnny Rocket’s space. And then that place went up for sale. So, two women went out looking for a new space. Eli went to South Beach, on Lincoln Road. And the other woman, whose very popular (her husband was a major landscape artist), she went to the Bakehouse. I am friends with both. I’m 18 years old at this point. They both come back to the Grove House and they say “We have to make up our minds. Which one do we want to take?” And both of these women explained what they were doing. Eli said “I have right now, under contract, I can get 7-10 store fronts where we can put artists and pay very little. We can change that whole space.” This was the early 70s. South Beach was a derelict area; you did not want to walk around there. But then the other woman said, “Oh but the Bakehouse is a bakery that’s been around forever! Marita’s Bakery. And it’s empty, in the outskirts of Wynwood. We can take that whole building and have it to ourselves and put studios and all that.” The board was divided between the two! So, one group went to South Beach and one group went to the Bakehouse. They opened them both up with artists and that’s how both spaces started. The Bakehouse didn’t have air conditioning for the first 5 years. Look at them now! And in South Beach – when Eli started bringing in all these artists that were producing great work, they started bringing in all the collectors. And they wanted restaurants, places to buy things, so that’s how things started developing. And then you have Wynwood. Now those artists are being pushed out and going to Little Haiti.

Yady Rivero: Okay I have just one more question. And then I’ll leave you…

Lilia Garcia: Oh, we talk too much.

Yady Rivero: No, no. It’s been fascinating. My last question is since we’ve been reflecting on the art community here in South Florida. What are some lessons we can learn in terms of improvement, or things that have happened in the past that you keep in mind?

Lilia Garcia: Well, considering my background and my interests and my purpose for joining the board – I think, not losing the Arts. Keeping them important and as a part of our lives – it has to be through education. I think that the Frost will show this in its exhibition. All the local artists in the show became the guides and the mentors for those coming up. The show can show that when it brings people in. So, I think that’s something to keep in mind. You don’t want an exhibit that just…especially after a pandemic where no one wants to go anywhere – you have to bring in people and come up with events. Especially history people.

Yady Rivero: Like an education program.

Lilia Garcia: Yes. It’s not just doing the event; it’s bringing people to the event. I would like to see it documented and accessible.

Yady Rivero: Thank you so much for taking the time to meet with me.

Lilia Garcia: You know I had a friend that would say, if it’s about the arts then it has a connection the Grove!

- Renée Ransom

As opposed to an oral history, the following text comes from email conversation between Renée J. Ransom, artist, and Amy Galpin, curator on May 22 and May 23, 2021. Ransom was active with the Miami Black Arts Workshop and two of her works are included in the exhibition, Place and Purpose: Art Transformation in Coconut Grove at the Frost Art Museum FIU.

Amy Galpin: Where were you born?

Renée Ransom: Winter Park, Florida. I went to Webster Elementary School in Winter Park, Florida and Hungerford High School in Eatonville, Florida. I also studied at Orange County Vocational School and Jones Business College in Orlando.

Amy Galpin: When did you move to Miami and why?

Renée Ransom: I moved from Winter Park, Florida, to Miami, Florida on May 3, 1979. Before moving on to Miami, Florida, I created numerous art décor craft creations during high school continuing to adulthood in the areas of “plaster crafts,” I participated in several art exhibits and shows. I obtained contracts in decorating parties, special events, weddings, and teaching specialty workshop classes.

On May 3rd, 1979, my sister Cynthia, owner of Flowers by Cynthia Floral asked me to come to Miami, to help fulfill creating 150 floral baskets for Mother’s Day. After fulfilling that event, she begged me to come to Miami to reside there and to help run the floral business. I did end up moving to South Miami, to help Cynthia. Upon coming to South Miami, I was introduced to Mr. Jack Dunn, the owner of Jack’s Place: Jack’s Famous Steak House on Grand Avenue, to sell my artifacts. Jack’s Place was two doors down from the Miami Black Arts Workshop.

Being at Jack’s Place, I was curious of the people coming in and out of this place a few doors down. I introduced myself, the first person I met was Dinizulu Gene Tinnie. Then Ernest Cason, Oya Besis, George Wrentz, Robert McKnight, and his brother Donald McKnight, Rubie Laffin, Roland Woods, the Director of the Project, and a host of others later. I was granted space to work there at the workshop. I began taking ceramic classes and basket weaving classes at the Web in Coral Gables. I started working part-time at “West Miami Ceramic Shop” in West Miami. I attended Helen Alteria painting specialty classes and ceramic pottery, learning hand building techniques, clay lifting, scrafetto, (a method in drawing designs into clay while moist). I begin taking ceramic tile pouring and pattern design classes. During this time frame, I was busy learning other skills and crafting, that truly helped me to advance.

As time moved on, one year, later my sister Cynthia passed away. I then moved to Coconut Grove, to reside on Charles Avenue. After a few months passed, I was hired to work at the Coconut Grove Girls Club. I was hired as the arts instructor to teach creative art décor/craft projects to summer camps and afterschool girls on Williams Avenue.

I would come by the Workshop to visit daily to say hello and to see what projects were going on in the community, I learned that the community highly depended on the artists at the Black Arts Workshop. Occasionally I would bring my art to work on. One day, I was approached by Roland Woods, the director, who told me their secretary is leaving, and the Workshop will be in need of a secretary. I expressed to Roland, that I have secretarial skills. He was not aware that I had those skills. He knew me only as an artist. I completed an application and took a typing test and a filing test indicating the different filing systems. He asked if I would like to have the job. I said “yes”!

I served as part-time secretary. I formatted proposals for grant funding to continue artwork throughout the community and helped Roland structure contracts for the artist for modifying and beautification projects improving the outer facing of businesses and homes.

The Miami Bahamas Goombay Festival was started by The Miami Black Arts Workshop. Yes, the Miami Black Arts Workshop was the home for artists that migrated from abroad to Miami – Coconut Grove, Florida. Roland Woods inspired me to structure my first proposal for a grant to teach: Arts for the Handicapped. A project I desired to teach as a home-base motivational project.

The proposal was submitted and returned approved from The Counsel of Arts and Science, the City of Miami. Roland, Dr. Ted Nichols, Dr. Marzell Smith and I, structured an overall afterschool project for the community youth sponsored by the Workshop.

Amy Galpin: Please tell me about your life in Texas.

Renée Ransom: Texas, is where it all started with health and well care for me. I attended A.T.I. Institute for massage therapy, North Richland Hills, Aromatherapy Chemistry I, II in Dallas, Reiki in North Richland Hills, Certified Herbalist in North Richland Hills.

I create "All-Natural Essential Oil" Body Care, Skin Care Products to balance the skin pH factor. I am a licensed massage therapist, a certified medical assistant, and a licensed esthetician. I am a therapeutic pottery specialist, a ceramic tile designer, a therapeutic art therapist, and I design interior and exterior art décor.

Amy Galpin: Thank you for sharing with me your memories of Coconut Grove and for telling me more about your life in Texas. We are so happy to present your work in the exhibition.

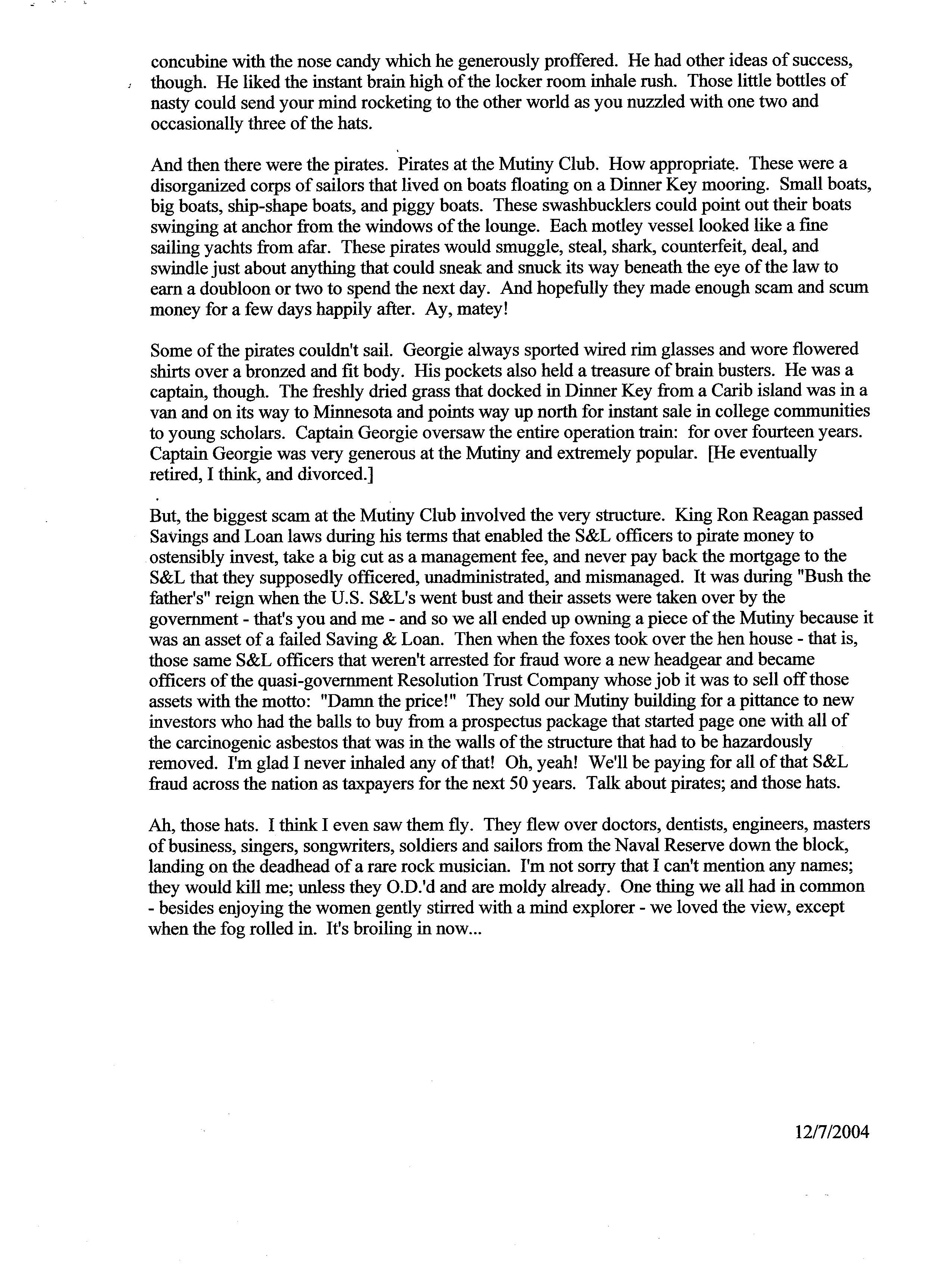

Renée J. Ransom, Clothespin Art Creation II (Dining Room Set), clothespins and fabric, 1981, courtesy of the artist, photography by Zachary Balber

- J.S. Rashid

Coconut Grove Resident and community leader J.S. Rashid and curatorial assistant Ashlye Valines sat down to discuss his work as a community leader and urban developer in the Grove during the ‘1980s and today. Rashid is the President and CEO of Coconut Grove Collaborative, now the Collaborative Development Corporation, whose mission is to rebuild the civic fabric of South Florida Communities.

This interview was conducted for the exhibition Place and Purpose: Art Transformation in Coconut Grove, 1968-1989 and took place on July 14, 2021.

Ashlye Valines: Where were you born?

J.S. Rashid: I was born in Chicago Illinois.

Ashlye Valines- And when did you move to Coconut Grove?

J.S. Rashid: 1985

Ashlye Valines: What were some of your most memorable places in Coconut Grove?

J.S. Rashid: Well, it’s in what was called, at the time, West Grove. There’s a couple of them, it’s hard to choose, like your children. “Which one is you favorite?” We have many favorites, or secret favorites. In this part of the Grove, they do the Goombay Festival. It’s right here on the strip and years ago, before I helped along with others, this was a four-way highway with no median strip and one of the things we changed… the business guru said, “if you’re going to have business you have to have traffic coming.” And the cars were going pass too fast because of the perception of crime. The perception was greater than the actual crime, but it’s always accelerated when it’s in a minority neighborhood because every incident here just has a multiplier effect. Even though the statics sometimes belie the associated fear, it was just as valid. It was something that you had to do something about. But the Goombay Festival takes place here, and the last Goombay that was held, I did it with the KROMA [gallery], I put on the last one, it’s kind of demised. The first year after they completed it, they suspended it while they were doing this work on the road and then one year they had it but the quandary was, you were kind of going in one lane when it used to be the whole street and they never surmounted that.

The other thing is, when I first moved to Coconut Grove I lived in, what is now called, the Village West, and I lived on little bit of the north part, close to Bird Avenue but in the Village West, and some Saturdays you would wake up and you would hear the sounds of some kind of festival, you would hear music and it really embodied, to me, the sense of village life. It was just really a simpler time, a simpler pace and really organic and natural, that’s just the lure of Coconut Grove. One of my favorite places was going to Peacock Park and around Bayshore Drive with whatever festival… I won’t say du jour but, whatever festival, and they used to seem like they had a lot of festivals. Every other month there was some kind of festival. It was really fun to, kind of, just stroll over there. Whether it was the Barnacle Fest, or the Mad Hatter, or the Art Festival or the Taste of the Grove, all those kinds of things, and that’s what Grove life was really like, and it was really good and the simplicity.