An Elegy to Rosewood

Further Research

In addition to the family heirlooms lent to An Elegy to Rosewood, Lizzie Robinson Jenkins provided further information gathered during her lifelong investigation of the 1923 Rosewood Massacre. These archival images are paired with personal reflections and anecdotes acquired through interviews and archival research.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

This shotgun house is believed to have been owned by Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier and husband Aaron Carrier, aunt and uncle to Lizzie Robinson Jenkins. Built around 1981, this house is situated southwest of the Rosewood historic Black cemetery adjacent to the only standing headstone of Martine Goins, a Black cofounder of the Rosewood township. It is surrounded by the Gulf of Mexico.

Robinson shares, “My mother, Theresa Brown Robinson, would visit her during weekends when she had saved up enough money to pay 25 cents for a roundtrip ticket on the historic Suburban from Archer to Rosewood. The east side of the house is where Aaron Carrier hung his mirror to shave.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

Lizzie Robinson Jenkins was born October 25, 1938 to Mr. and Mrs. Ura and Theresa Brown Robinson on the family’s farm in Archer, Florida. A family of six lived happily in a four-bedroom shotgun house.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

Lizzie Polly Robinson was born in this house on the family’s kitchen table. October 25, 1938, Tuesday morning, 9am. When Robinson was born, and her umbilical cord was cut, her father, Ura Robinson, took her in his arms, opened the door, lifted her toward the sky saying, “Bless my baby!”

Lizzie Robinson shares: “I was a blessing to the family by researching and mastering the history of a people and a nation. The task is not easy, but needed and as my mother often reminded me, ‘Someone has to do it.’ Many years I struggled and suffered silently and agonizingly. Few complaints. I stood in solidarity, alone with my husband, John. He was my bridge over troubled waters, the joy of my salvation, and my rock. Thank you, John, for all the love and respect for my mother.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

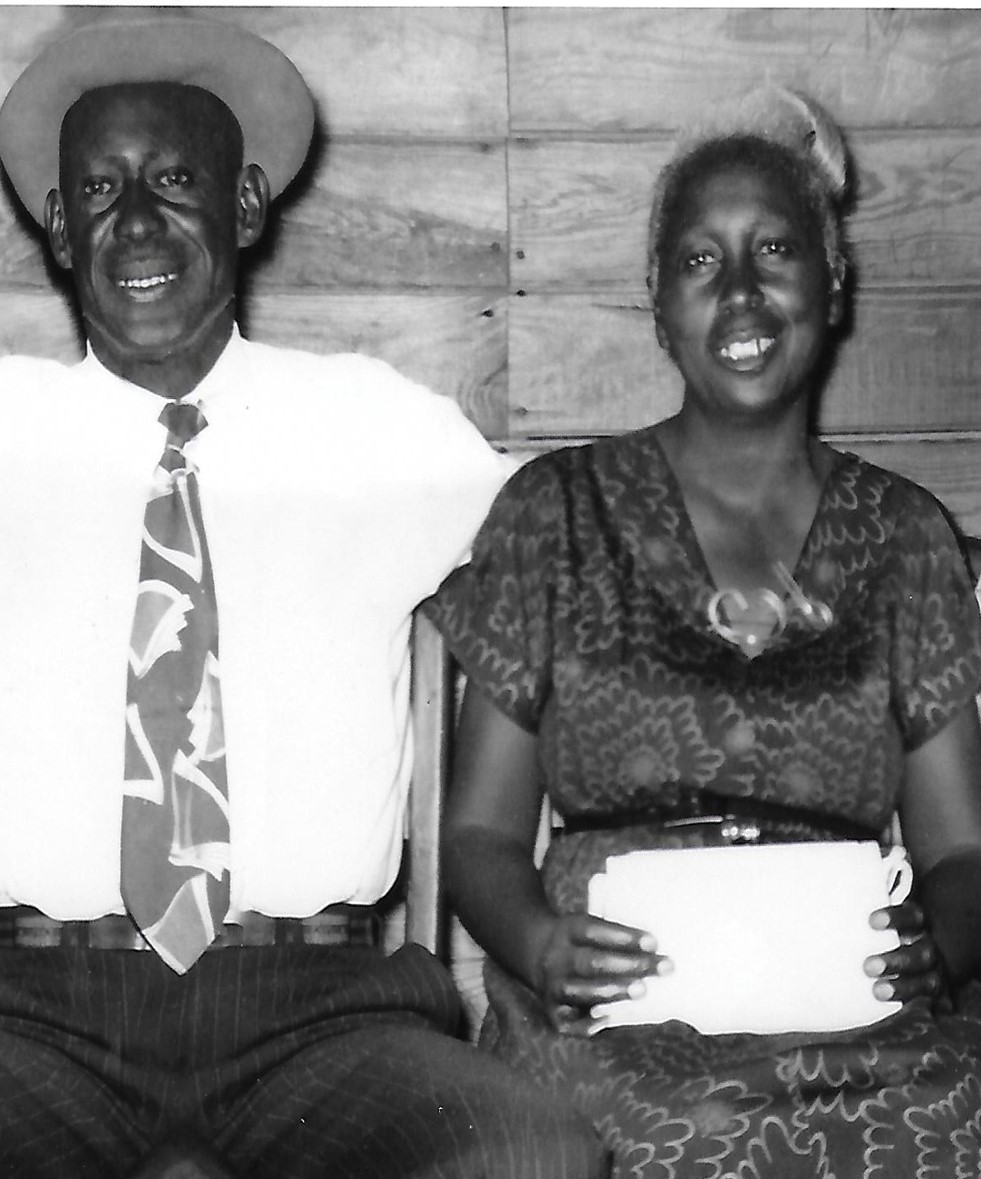

About the emotional hardship endured by assault victim and Rosewood Massacre survivor, Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier, Jenkins states the following:

She suffered the agony of defeat for twenty-five miserable years after the Massacre. She was on the run from conspirators, The Ku Klux Klan, and Jim Crow boys who made her life a living hell. They did not want her to discuss the Rosewood Massacre with the public. According to family letters, she moved more than ten times, changing her name on five separate occassions. She died lonely with her sister Theresa Brown Robinson, my mother, by her side in a Tampa, Florida.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

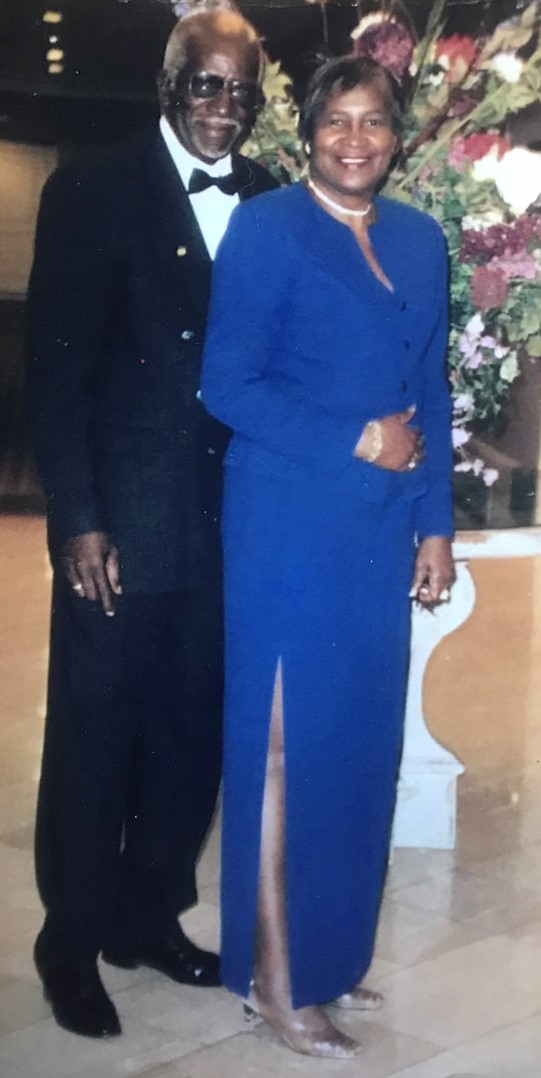

Founder and co-founder to the Real Rosewood Foundation, John M. Jenkins, Sr. and Lizzie R. Jenkins have dedicated their lives to keeping the Rosewood history alive to satisfy and justify the demand of Lizzie’s mother Theresa Brown Robinson to “research, authenticate and document the facts of Rosewood’s history.”

Robinson explains: “John initiated the Rosewood peace and healing ceremony wherein we returned to Rosewood, invited family and friends to meet us in the park, and sang, prayed, and consecrated the soil. Some of our white Rosewood neighbors would come out and stand around as spectators, never joining us, but never disrupting us. They would smile and leave after a few minutes. We also cooked and sold food to the crowd. This is the type of activities that happened during the lifetime of Rosewood residents.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

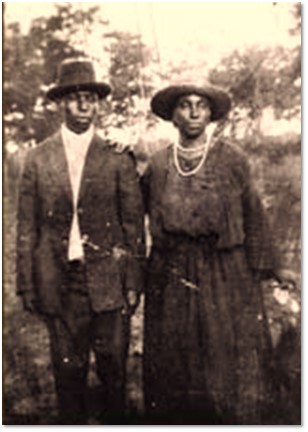

Pictured here are Lizzie Robinson Jenkin’s great grandparents, once enslaved.

About her research, Jenkins recounts the following:

Grandpa Richard Sams was from Waco, Texas. At age 15, he was kidnapped and brought to the Jackson, Mississippi auction block where he first saw his future wife, Juliann Sams. She he was 13 years old in 1839, from the Parchman Farms in Parchman, Mississippi. The night the white insurrectionists came to take her from her parents was the worse day of her life. She never saw them again, lost contact with everyone she loved, and hated them for the rest of her life. She was tied up with barbed wire and forced to walk to Jackson, Mississippi where she was sold to the highest bidder, James M. Parchman, the son of the Parchman Farm heirs. Six months later, she completed her forced walk with several other enslaved African Americans which ended in Archer, Florida, where I live today with my husband. She was violated all the way and hated the hired gunmen that rode the horses. Who does not believe history doesn’t repeat itself? Same thing happened in Rosewood to her granddaughter, Mahulda Gussie Brown Carrier, 84 years later.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

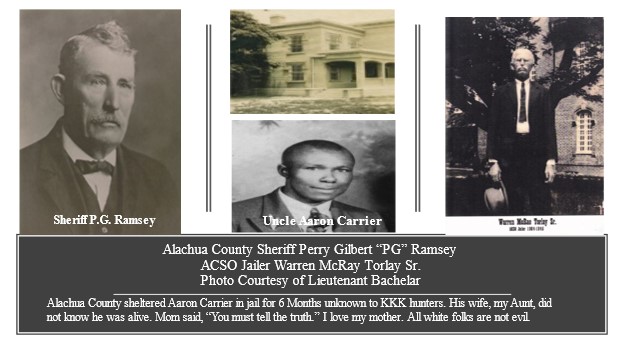

In sharing her lifelong research of Rosewood, Lizzie Robinson Jenkins considers the role of Sheriff Perry Gilbert “PG” Ramsey vital in understanding the various nuances that exist when studying race relations in 20th century Florida. As a white man in a position of power, Sheriff P.G. Ramsey successfully hid Aaron Carrier—who had been falsely accused of assaulting a white woman—in the Alachua County Jail without giving his location away to Ku Klux Klan members. This act saved his life.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

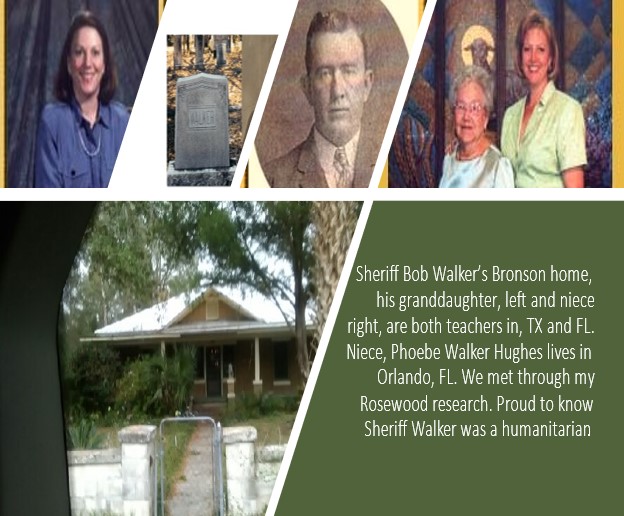

When Lizzie Jenkins learned of the actions of Levy Coutny Sheriff Robert “Bob” Elias Walker, she traveled to visit his living descendants, pictured here, and spoke to them of the oral histories passed down through the generations. Robinson’s own mother once told her, “Sheriff Bob Walker worked 96 hours straight to save the Rosewood people because he cared and did not want anyone to die on his watch.” Robinson points out, he was fired for his act of humanity and today his photo does not hang in the Levy County halls of famous Levy County Sheriffs.

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

About this image, Lizzie Robinson Jenkins writes:

“This Sumner shotgun house is where the Black sawmill workers lived. During the violent acts of the Rosewood Massacre, the workers were told to send their family members on the train to Archer and/or stay quietly in their homes during the Massacre. I understand some sent their family east and others sheltered safely in the homes. When the fighting was over, the Sumner workmen returned to work as if nothing had happened, winking at each other, with deep satisfaction as winners. However, they were very involved with the fighting resistance.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

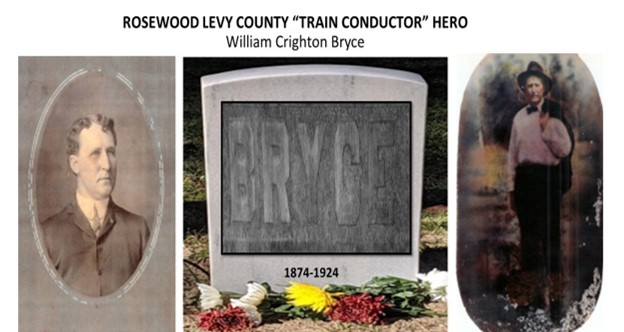

Jenkins states, “Community members share the story of the Bryceville Brothers with great emotion. As white men, the two brothers used their privilege to aid Rosewood survivors and lead them to safety. Robinson met with William Crighton Bryce’s great granddaughter who shared the family story passed down to her by her mother. He was killed in 1924 while riding his horse by an unknown assailant. To this day, Bryceville, Florida, is a lumber town.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

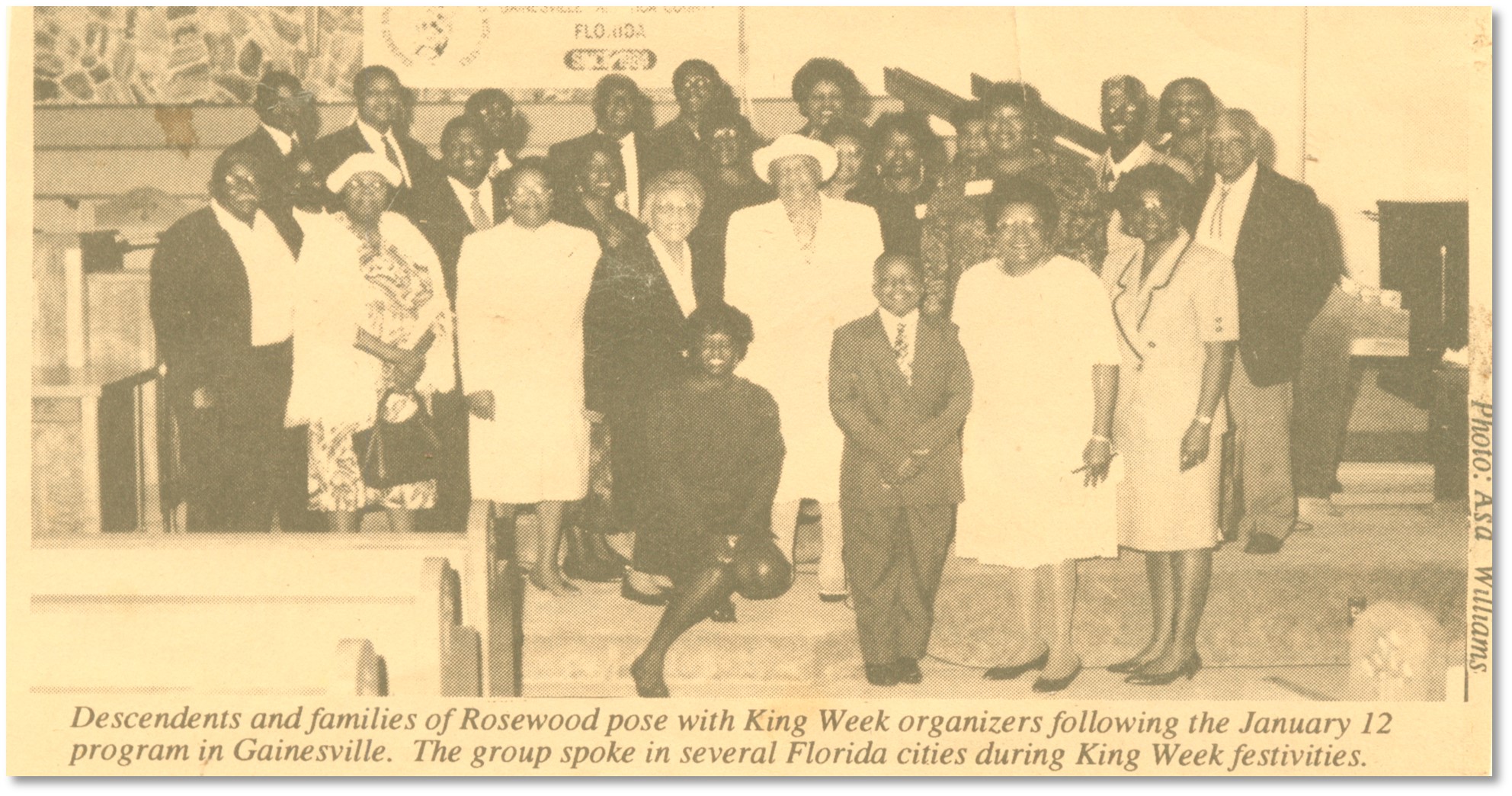

Jenkins writes, “The Rosewood survivors in 1992, Gainesville, Florida. I am standing bottom row, right. Most of them are now deceased.”

Image courtesy of Lizzie Robinson Jenkins

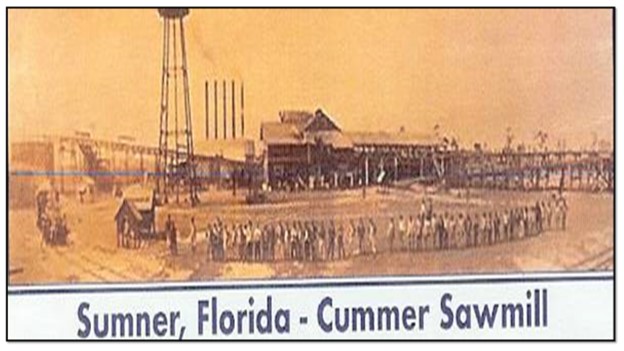

Levy County Sawmill located in Sumner, Florida.