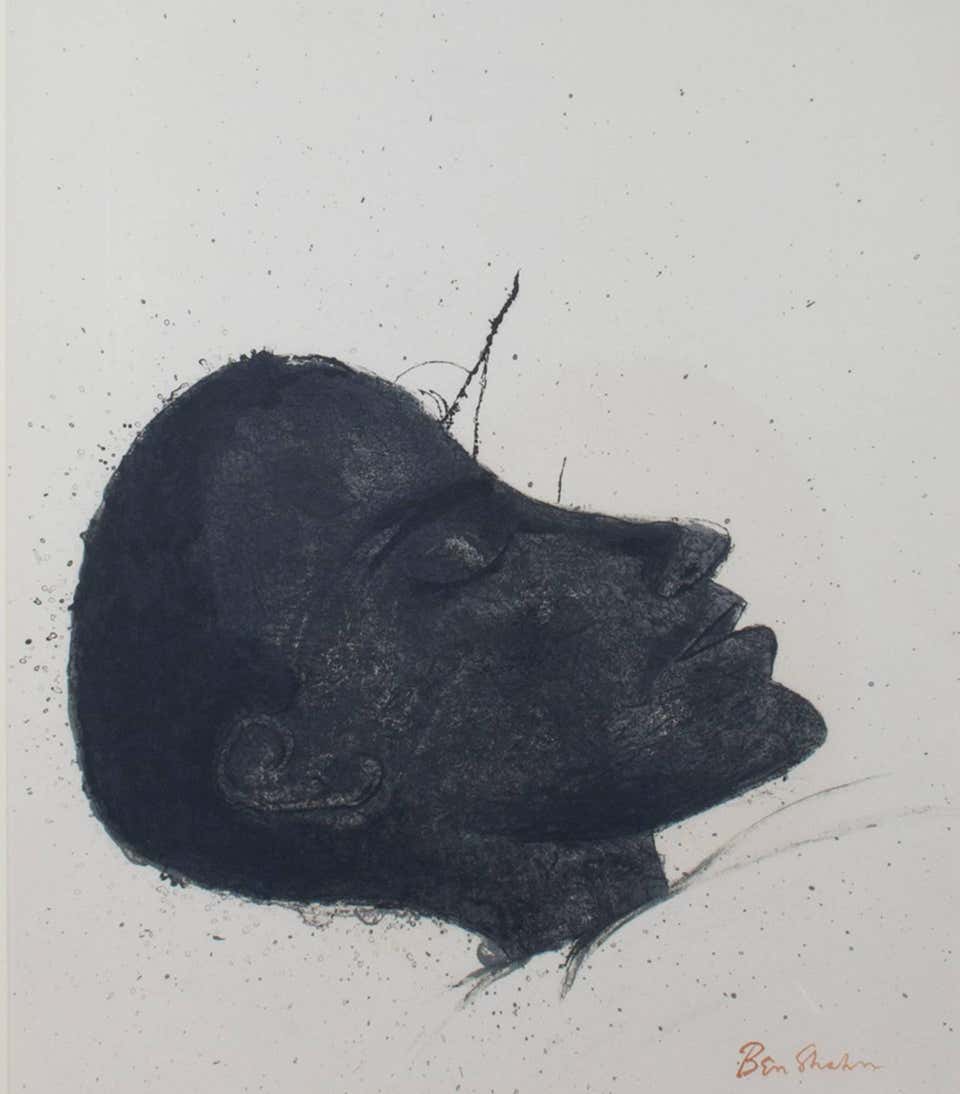

Luis Cruz Azaceta (American, born in Cuba, 1942), Gun Shots II , Monoprint on paper, 1989, Museum Purchase through a gift from Sam Oroshnik, FIU 92.10.6

After the end of the Cuban Revolution, Luis Cruz Azaceta left his home in Cuba for the United Stated in 1960. At age eighteen, Azaceta settled in New York where he finished his studies at the School of Visual Arts. Gun Shots II is one of many works by the artist dealing with issues of urban violence and psychological terror—both of which he witnessed firsthand as a youth in a country undergoing mass upheaval. The languid figure pictured at center has his face raised, facing upwards in apparent agony, mouth agape and eyes bloodshot. The letters G-U-N are superimposed in front of the figure, encasing him within the backdrop of large, bruise-like circles. As viewers, we are confronted with these three elements – the anguished man, the word “gun,” and the circular wounds. In this instance, Azaceta presents a lone moment of physical discomfort and a mental warfare that Azaceta often refers to as “psychological violence.”

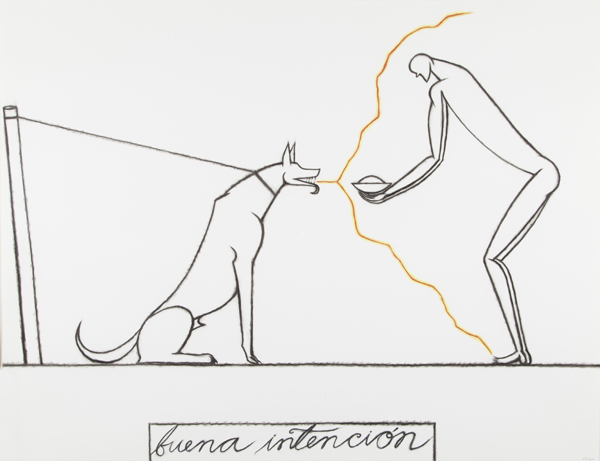

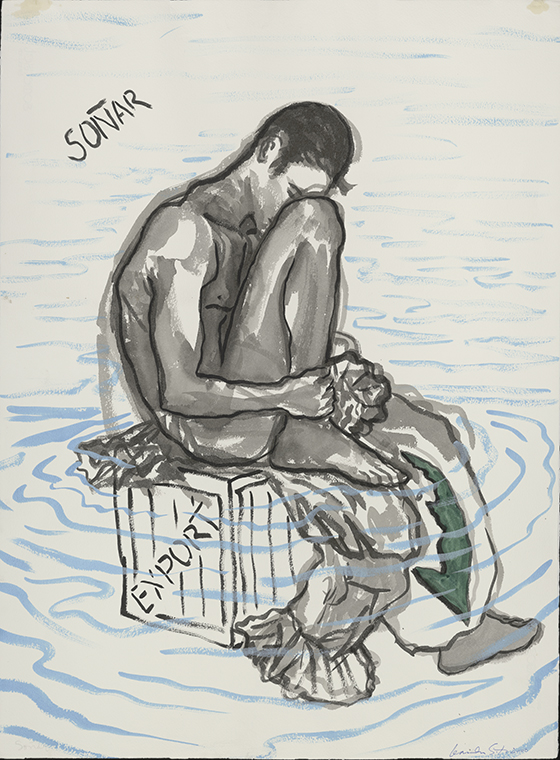

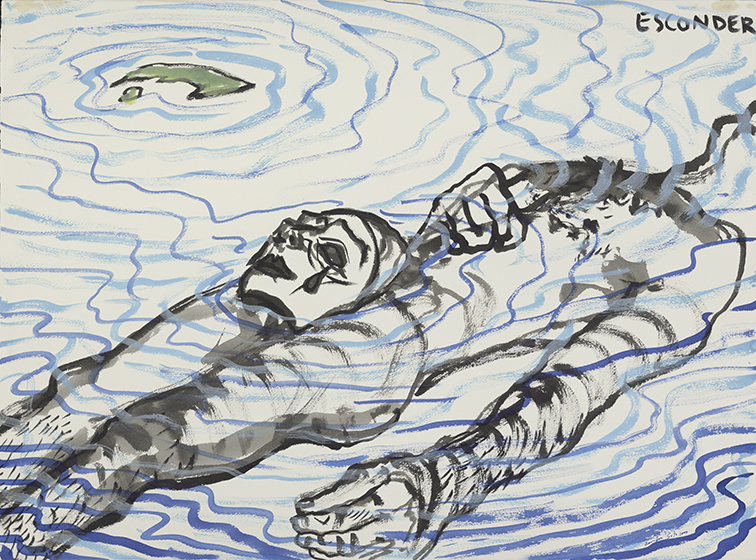

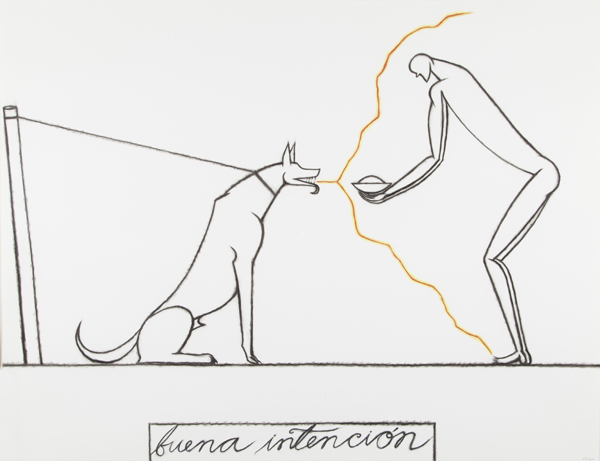

José Bedia (Cuban, 1959), Buena Intención, Conté crayon on paper, 2001, Gift of Mrs. Ruth Shack in memory of Richard Shack, FIU 2013.2

Bedia is well-known for his evocation of Cuban imagery and incorporation of African traditions in his art. Many of his works are inspired by his Santería faith and Christian beliefs and include sacramental imagery as well as mythical elements. Bedia portrays empathy with a powerful, yet modest visual approach. Empathy is understanding or being in tune with a feeling experienced by others, rather than just observing emotions. Art created by Bedia and others, can teach empathy. There’s a line of energy emerging from the dog to the recipient, which symbolizes their substantial connection. Bedia chooses to include text not only in this work, but many others, to give the audience a literal way to engage with the work of art. At first glance the imagery could be interpreted as an act of malice (relating the social distance between the participants), but the text, translated into English as “good intention” reveals the human subject’s desire to feed the dog.

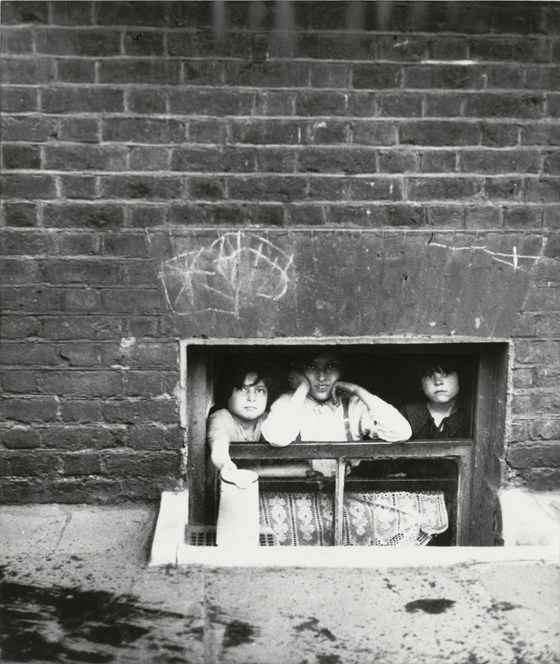

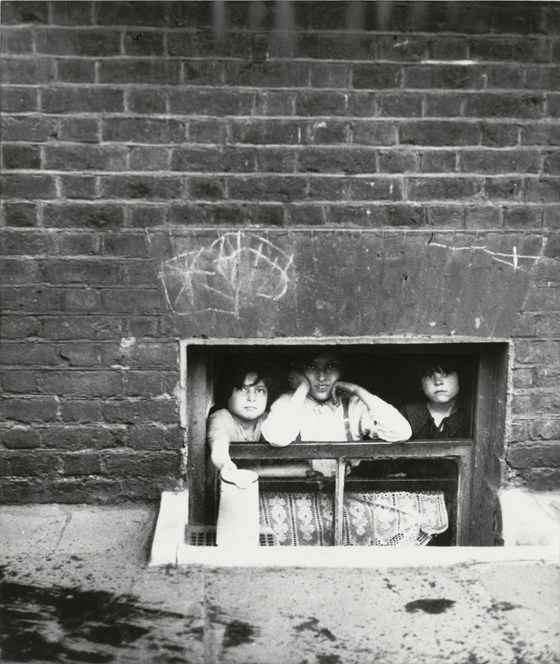

Bill Brandt (English, 1904–1991), Bethnal Green, London, Gelatin silver print, 1934, Gift from the collection of Jules and Jordana Schneider, FIU 2018.8.11

Born in Germany and raised in London, Brandt began his photography career as a social documentarian. In his second book, A Night in London (1938), he recorded the effects of World War ll across the city. Many of the photographs in the series were taken at night, without flash, during the city’s blackouts. Influenced by artist and lifelong friend, Brassaï (French, 1899-1984), Brandt’s images possess a heightened ambience and a sense of place. This image depicts children on the window of a basement apartment staring at the people walking by the street. The photograph demonstrates urban living conditions that can be crowded and devoid of sunlight. Bethnal Green, where the image was taken, is a neighborhood in the East End of London which lies 3.3 miles northeast of Charing Cross, a major crossroads in London and historically considered to be the center of the city.

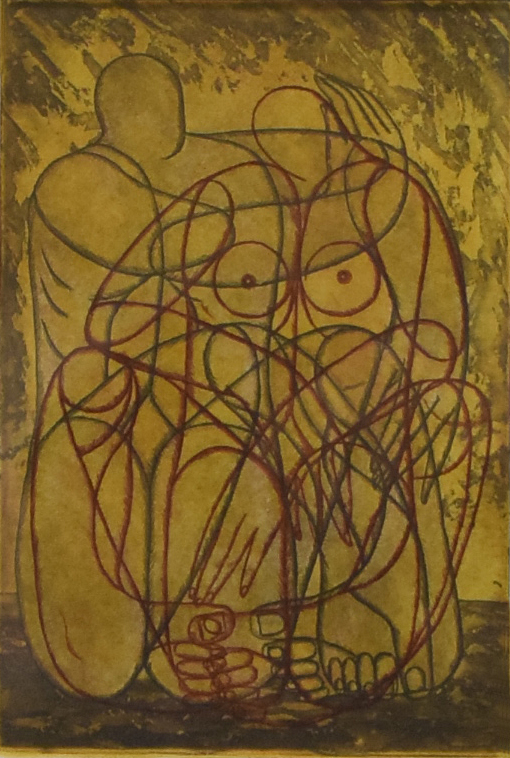

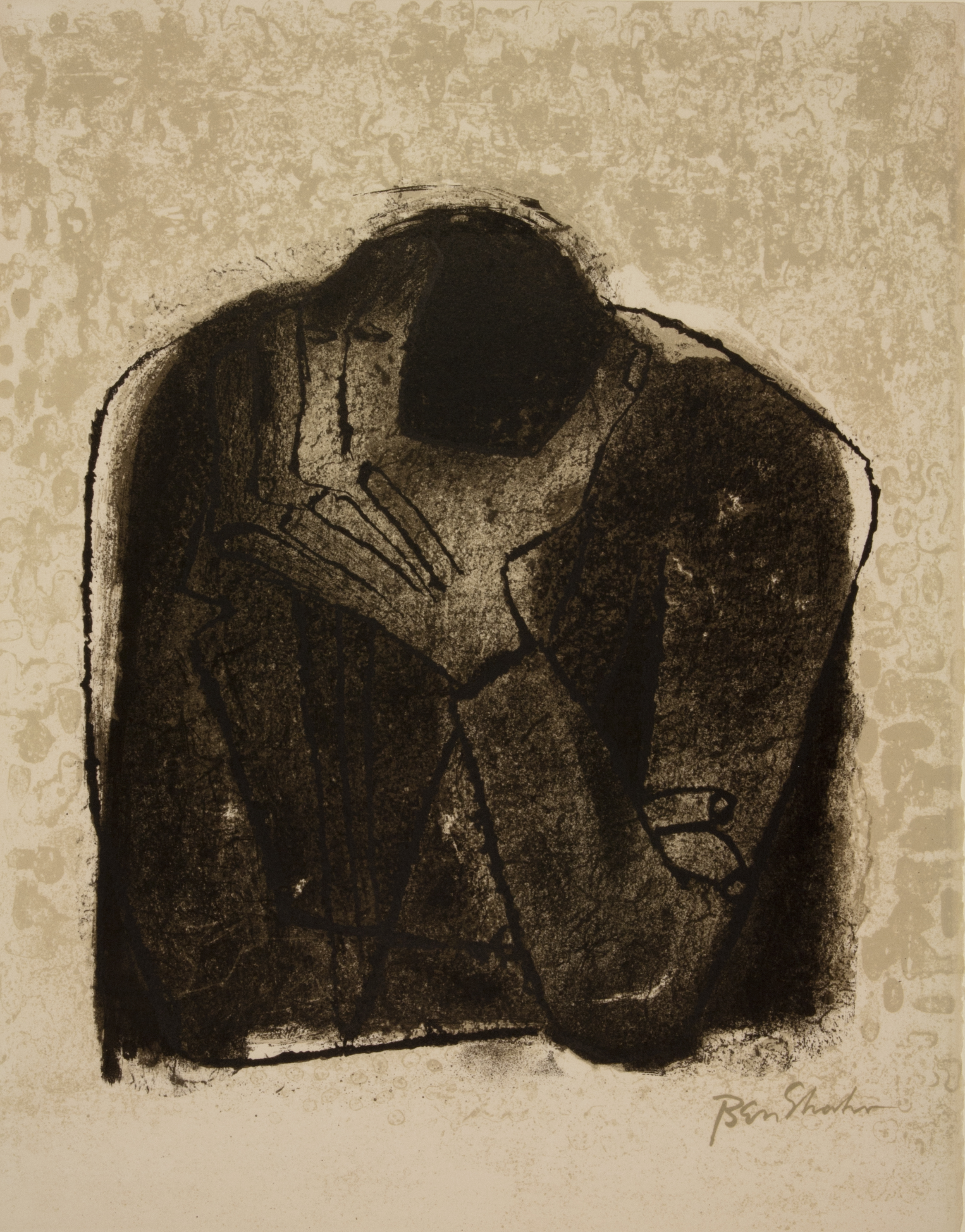

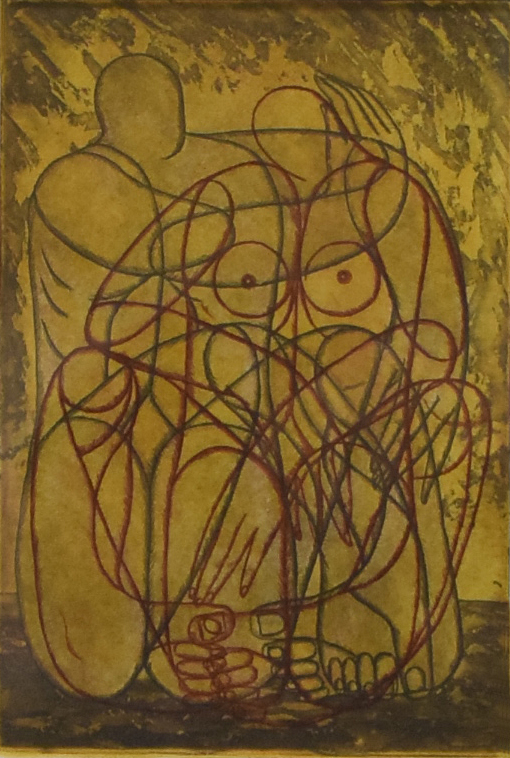

Gábor Korányi (Hungarian, b. 1952), Analysis (Comforter), Etching and aquatint, 1997, Gift of Mr. Serg J. Rioux, FIU 2000.001

The etching process, where a negative impression is first marked against a metal plate, is intricate and labor-intensive. It involves rinsing, bathing, scrubbing, heating, and eventually pressing the plate onto moistened paper. Artist Gabor Korányi is a vocal advocate of this method, often emphasizing the rich potential for artistic expression within each step. This etching in particular features an entanglement of lines and limbs characteristic of Korányi’s work. The artist draws the viewer into the emotional struggle experienced by the subjects. Two abstract figures float atop a ground of ink, providing a stark visual contrast between the two modes of mark-making. One set of lines represents the internal emotional system, while the other set of lines represents what is visible from the outside. Korányi is selective with his detailing, allowing viewers to gauge for themselves where one figure ends and the other begins both literally and metaphorically.